Ask Ariely: On Social Solutions, Date Decisions, and Prompt Payments

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Hi, Dan.

I work for an investment banking firm where 90% of the employees are men. I’m the only woman on my team, and ever since I joined, my teammates have treated me like the office plant. They make lunch plans without including me and say hello and goodbye to everyone except me. Generally, they pretend I don’t exist. I don’t think they are doing it to be hurtful—I just think they’re not sure how to befriend women. What can I do to change this?

—Jamie

Social isolation is difficult and painful, and I’m very sorry about your experience. Sadly, it is difficult to change the social norms of an entire group at once. An easier path would be to change the behavior of one colleague at a time; direct interactions will help them to see you as a whole person. Why don’t you try to invite one of your co-workers for coffee or lunch every week? In time, this will change the overall atmosphere in the office.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Every time I suggest an idea for a date, my husband questions whether I’ve picked the very best option. For instance, I once suggested that we dine at the Thai restaurant down the street. Instead, he perused Zagat until he found a “better” option. And a month ago, I suggested we go on a cruise using a company my friends like, but he insisted on researching alternative companies before committing. We still haven’t made any firm plans.

From my standpoint, I’d rather make a “good enough” decision and enjoy the experience, however imperfect. My husband points out that his research often yields objectively better decisions. Who’s right?

—Caroline

In social science terminology your husband is a “maximizer” (someone who tries to make the best possible decision), and you are a “satisficer” (someone who tries to choose from within a range of good options). Lucky for you, the research suggests that your strategy is the right one.

The psychologist Barry Schwartz and colleagues did a study in 2002 comparing the two types of decision-makers. They found that maximizers had lower levels of optimism, happiness, self-esteem and even life satisfaction. They were also less happy with their daily decisions, and they tended to regret the decisions they made more often. So while your husband may indeed be finding the best-rated restaurant, movie or cruise, in the process he’s probably taking away a lot of his and your joy.

Here’s what I’d suggest: Instead of making date decisions together, take turns being in charge. That way, half the dates will go smoothly—and in the other half, you will get to practice your patience.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m a scientist, and I recently volunteered to be part of my professional society’s membership committee. What is the most effective way to get people to pay their membership dues? Reminders? Guilt? Calling them up and begging them?

—Stephanie

My guess is that your members are generally interested in staying members, but they just don’t want to pay “right now”—whether that means today, tomorrow or the next day. To fight this kind of procrastination, I would make it more tempting to pay now. For instance, host an attractive webinar that is open to paying members only. That would give your members a good reason to pay promptly.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Tardy Travels, Past Prejudices, and Dangerous Drivers

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Hi Dan,

I am a frequent flier and I often have to deal with annoying delays, which can seriously affect my mood. What can I do to get less upset when a plane is late?

—Hailey

Our happiness is largely influenced by our expectations; in the case of flying, that means our expected departure and arrival times. My friend Ory was once booked on a flight whose take-off was delayed for seven hours, leaving all the passengers upset and complaining. But when the flight attendants announced that the delay would actually only be five hours, people cheered: compared to what they were expecting, a five hour delay seemed like a good deal. So the next time you take a flight, add two hours to the expected length of the trip and write down the later arrival time in your calendar. If the delay ends up being less than two hours, you’ll be happy.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Can behavioral economics teach us anything about Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam’s blackface scandal? I’d like to think I would never have worn offensive makeup, or done even worse things like owning slaves or joining the KKK. But how do I know what I might have done if I lived in another time and place? I don’t think I am a racist, but in a different society, would I too behave as a racist?

—Will

One of the fathers of social psychology, Kurt Lewin, posited that behavior is always a function of two inputs: the person and the environment. Acts of racism, sexism and other types of harm usually don’t originate from a few “bad apples,” but from cultures that explicitly or implicitly support such acts. So while we shouldn’t excuse acts of hate, we certainly need to recognize the systemic forces that shape what we consider normal or acceptable. Ending racism is not just about getting individuals to change, but understanding how our environment and institutions uphold prejudice in both obvious and subtle ways.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My grandfather is a bad driver. Everyone in the family knows this, but we have accepted it as a fact of life. Recently, I asked him to drive more carefully, while emphasizing that I really care about him. He told me that I have nothing to worry about, since he is an excellent driver! What can I do to make him drive more carefully?

—Limor

Driving is the classic example of “the better than average” effect: almost everyone thinks that they are better than average drivers. This means that trying to convince your grandfather that he’s a bad driver is going to be difficult. Instead, I would start by trying to help focus his attention on the road and not on other things. First, try to get him to stop using his phone while he’s driving. You could also get him a GPS device that speaks directions out loud, so that he won’t have consult a phone or written directions when he’s driving. Finally, to encourage him to drive less, you or other family members could volunteer to drive him from time to time, or introduce him to one of the available taxi apps.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Flexibility Fees, Climate Commitments, and Sensible Surprises

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I know that you’ve often written about money as a motivator. This semester, I would like to join a yoga class that requires a substantial one-time registration fee. Will paying this amount in advance motivate me to attend regularly to make up for the money I’ve spent?

—Jeff

Yes, we’re much more likely to do things when we commit to them in advance and have sunk costs. One challenge with this approach is that, over time, you might forget that you have paid that large initial fee. I would recommend that you print the receipt from your one-time registration fee, laminate it and attach it to the door of your refrigerator. This would not only be a constant reminder to attend your yoga class but also might be useful encouragement to eat more healthily.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am very concerned about climate change, and I try to minimize my own consumption. I don’t drive much, avoid products packaged in plastic, grow as much of my own food as I can and use video chats with my relatives instead of flying to visit them. At the same time, I know that my individual choices and sacrifices are not having much of an impact on this gigantic problem, so I find it hard sometimes to keep to these restrictions. How can I increase my motivation and stick to my principles?

—SF

Climate change is certainly one of the toughest behavioral issues, for exactly the reason you cite: Our individual actions feel like a drop in the bucket, and this discourages us from acting.

One of the best ways to boost your motivation is to use the people around you. You could, for example, rally some friends, neighbors, co-workers and family members to join you in your effort to limit consumption. You might start by asking them to commit to one action, such as putting a five-minute cap on showers, and then all of you could track your success together. By acting together, you will feel that your impact is larger.

One example of such motivation comes from a study recently conducted for the grass-roots political group Postcards4VA by the social psychologist Brett Major, described in the journal Behavioral Scientist. The study looked at what motivates people to volunteer more for political action. As you might expect, those who had joined political groups were more likely than the unaffiliated to act politically. Group participants were also more likely to have a positive experience and to intend taking future action; they were also less likely to get burned out. So before you give up on your cause, call a few friends.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I live abroad. My girlfriend has never been to my hometown, and my parents are always asking me to bring her when I go to visit them. In October I plan to do that, though my family doesn’t know. What would make them happier: to surprise them when she shows up with me or to tell them in advance and let them enjoy the anticipation?

—Miquel

Surprise and anticipation can each lead to happiness. In your case, surprising your parents might make the first hour of your visit more exciting for them—but after that, it might take a few weeks for them to get over the shock. In this case, I would advise you to give them plenty of time to look forward to your joint visit.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Opposing Opinions, Feeling Failures, and Adjusting Activities

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently learned about research showing that when people hold extreme beliefs, giving them data that contradicts their basic opinions actually strengthens those beliefs! Does this mean that there is no way to change the beliefs of people with extreme opinions?

—Jordan

Changing people’s opinions is indeed difficult, but there is hope. With people who hold extreme views, one paradoxical finding is that presenting them with even more extreme arguments in support of their beliefs persuades them to moderate. In a paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2014, Boaz Hameiri and colleagues describe a citywide intervention in Israel where they used this approach in an ad campaign about the Israel-Palestine conflict. The ad campaign was designed to try to change the opinions of right-wing Israelis who oppose peace.

The ads presented the participants with absurd claims about the benefits of the conflict—for example, that it’s good for camaraderie and morality and helps to create the unique culture of Israel. The results showed that the campaign changed minds: From what they said and how they reported voting, those with right-wing views became more conciliatory and cut back their support of aggressive policies, compared with residents of a comparable Israeli city without the ad campaign. The researchers hypothesize that the intervention succeeded because the ads caused people to more deeply consider their own beliefs.

___________________________________________________

Hey, Dan!

Why do we believe we can learn from our own mistakes but blame other people’s failure on their personalities and/or lack of sufficient skills? Has this “one-way street” phenomenon been studied?

—Darin

You are describing behavior that falls under the heading of what social psychologists call the “fundamental attribution error.” In general, we tend to see good things that happen to us as the product of our own doing and bad things as the result of outside circumstances. Conversely, we tend to attribute good things that happen to other people to external circumstances and bad things to their own doing.

We believe that we can learn from our own mistakes because those mistakes aren’t really about us. We think they involve external circumstances that we can learn to handle better.

Can we learn to override this type of judgment? I spent a lot of time in Silicon Valley recently, meeting with executives of startups and venture capitalists. I was struck by what often happens when a startup fails: People in Silicon Valley approach the setback much less negatively than the rest of the world does. Executives sometimes even look at their colleagues’ failure in a positive way, as a sign of experience and learning.

Can we generalize from Silicon Valley to the rest of the world? I’m not sure, but it seems to me that we can change the way we look at other people’s failures, and maybe even limit the blame we assign to them, as we would with our own failures.

___________________________________________________

Hi, Dan.

Let’s say that your regular activities include things like playing poker with friends every week or gardening every weekend. How do you decide when to keep on going with these activities—or stop and try something new?

—Joanne

Questioning the value of our routines is good, because it can help us to stop doing things we no longer enjoy. It’s bad, however, because such questioning gets in the way of whatever happiness the activity gives us. So I suggest that you question yourself—but only for a short time. Perhaps take the last week of December to evaluate how much pleasure you get from your leisure activities—and consider what you could do instead.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Better Brews, Money Management, and Flirting Forays

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m a fan of craft beers, and when I hear about an exciting new one, I’ll get a case or two and invite some fellow aficionados to share the experience. But as we crack open the new beer and sample it, I almost always find myself disappointed. Why does this happen so much?

—Ben

Your latest beer may just not be that good, but I think something else is probably going on here: Your heightened expectations are working against you. Raised hopes can influence the way that we experience something, for good or ill, depending on the gap between expectation and reality.

Imagine, for example, that the new beer you just bought measures an objective eight on a beer connoisseur’s 10-point scale. It’s a good beer, but not an amazing one.

If you had been hoping that your new brew would be a nine, your expectations can “pull up” the way that you experience the beer, making it taste as if it really is a nine. Your heightened expectations would heighten your experience.

On the other hand, if you were expecting a 10 as you raised your glass, the gap between the beer’s objective eight-point quality and your 10-point expectations will be too large to bridge—so large, in fact, that you’ll be disappointed relative to your expectations and feel like you’re drinking a mere seven.

All of this means that the trick to happiness (with beer as with much else in life) is to tame your expectations. Maybe try telling yourself that your latest brew is unlikely to be a 10, or remind yourself that the odds that your next beer will be spectacular are very low—and then be ready to enjoy it if that first quaff surpasses your less-than-great expectations.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve set myself a weekly budget of $500, which should cover groceries, lunch, coffee and nights out. I used to put everything on my credit card and try to keep track of my spending in my head, but I inevitably wound up spending more. To fight this credit-card temptation, I started taking out $500 in cash every Friday and spending only that. This strategy leaves me more aware of my outlays—but I’m still running out of cash by Thursday. What else can I do?

—George

Your dedication is impressive. Having a budget for discretionary spending isn’t easy, but it is the first important step toward better finances. It’s also good that you’re managing your weekly budget without credit cards, which are designed to make it hard for us to remember how much we’ve spent.

With that in mind, let me suggest two things. First, instead of using cash, switch to a prepaid debit card that you load with $500 a week. With cash, you tend to estimate how much is left just by looking at the piles of bills you have; the debit card can tell you after each transaction exactly how much is left in your weekly budget.

Second, start your budget week on Monday, not on Friday. With your current method, you’re giving yourself the largest amount of money to start the most tempting part of the week—the weekend—which leaves you more likely to overspend. If you start your budget week on Monday, you’ll be more likely to try to save some cash to have a fun weekend.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

What is the most effective pickup line?

—Janet

A good pickup line should show some interest but not too much, and it should put the burden of proof on the other person. I’d suggest trying, “You don’t seem like my style, but you intrigue me.”

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Common Cents Lab Unveils Millennial Financial Regret Spending Report

New report seeks to measure whether spending can make you happy

SAN FRANCISCO, CA–(Marketwired – Sep 12, 2017) – and Durham, NC Common Cents Lab, a financial research lab at Duke University supported by MetLife Foundation, today unveiled its first ever Millennial Regret Spending Report.

“While it’s common to regret the last thing we ate, it may be equally common to regret the last thing we bought,” said Dan Ariely, Professor and behavioral economist. “The feeling of regret, while not pleasant, may serve as a teaching moment to help us understand what we enjoy and what we don’t enjoy. By systematically understanding the things people regret, we can design systems that encourage us to spend our money on things that make us happier.

Conducted in partnership with Qapital, a fintech app focused on helping people save and spend better, the new study surveyed 1,000 Americans between the ages of 20 and 36-years old to identify which purchases they regarded as either most regretful or most satisfying. Through this effort, the team of behavioral economists isolated four positive personal financial habits that others may emulate to improve financial wellness and fulfillment.

1. Put the Essentials on Autopay

Participants were asked to rate how satisfied they were about recurring versus nonrecurring expenses across a number of categories. Almost universally, millennials rated their regret roughly 10% lower for recurring items. Since most recurring items are paid automatically, the idiom “set it and forget it” may carry more meaning than we thought.

Like millennials, others can limit the angst of rent and insurance payments by placing them on autopay. At the same time, make the payments you’re most likely to regret more obvious by using cash or one-time payment methods.

2. Spend on Enrichment and Others

Millennials reported being most satisfied when spending on necessities (utilities, rent) or personal enrichment (community, education). The study also tracked what times of the week and year produced the most satisfying purchases. Seasonally, those purchases made near Thanksgiving and through the first two weeks of December produced nearly 90% satisfaction as compared to months like October and February that dropped below 50%.

The lesson is that guilty pleasures often come with a heaping of regret, and that the greatest fulfillment can be gained from purchases that enrich your own life or are made for others.

3. Limit Impulse Purchases

The data clearly shows a greater level of fulfillment (roughly 70%) for purchases critical to living such as rent, healthcare and groceries over impulse purchases (near 50%) like digital purchases, coffee shops, and fast food. Similarly, those purchases made on Wednesdays were nearly five percentage points more satisfying than those made on Saturday.

The takeaway is that decisions made independent of the pressure and the heat of the moment can improve your overall financial happiness.

4. Sweat the Small Stuff

That final tally for that $4 latte may be much more in the long run, according to the survey findings as Millennials tended to regret smaller purchases much more than larger ones. On average, respondents reported a high level of satisfaction for purchases taking up a larger portion of their monthly income.

“Individually, these lessons seem intuitive, but taken together as a lifestyle, they can provide a blueprint for living a much more satisfying financial life,” said Kristen Berman, co-founder of Common Cents. “Interestingly, these are lessons that can be applied regardless of income level as a guide to improved financial decision making.”

A full copy of the Millennial Financial Regret Spending Report is available by request or can be found at http://advanced-hindsight.com/millennial-financial-regret-spending/.

About The Common Cents Lab

The Common Cents Lab, supported by MetLife Foundation, is a financial research lab at the Center for Advanced Hindsight at Duke University that creates and tests interventions to help low- to moderate-income households increase their financial well-being. Common Cents leverages research gleaned from behavioral economics to create interventions that lead to positive financial behaviors. The lab is led by famed Behavioral Economics Professor Dan Ariely and is comprised of researchers and experts in product design, economics, psychology, public policy, advertising, business administration, and more.

To fulfill its mission, Common Cents partners with organizations, including fintech companies, credit unions, banks, and nonprofits, that believe their work could be improved through insights gained from behavioral economics. To learn more about Common Cents Lab visit www.commoncentslab.org.

About MetLife Foundation

MetLife Foundation was created in 1976 to continue MetLife’s long tradition of corporate contributions and community involvement. Since its founding through the end of 2016, MetLife Foundation has provided more than $744 million in grants and $70 million in program-related investments to organizations addressing issues that have a positive impact in their communities.

Today, the Foundation is dedicated to advancing financial inclusion, committing $200 million to help build a secure future for individuals and communities around the world.

To learn more about MetLife Foundation, visit www.metlife.org.

Find the original post here.

Ask Ariely: On Financial Feelings, Polling Places, and Meaningless Messages

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Why is society structured around the accumulation of wealth? Is this part of human nature, and is it the best way to achieve happiness?

—Annie

Most of us believe that more money brings more happiness—and the wealthy are no exception. In a 2014 survey of very wealthy clients at a large investment bank, Mike Norton of Harvard Business School asked clients how happy they were and how much money would make them really happy.

Regardless of the amount they already had, they responded that they’d need about three times more to feel happy. So people with $2 million thought they could achieve happiness if they had $6 million, while those with $6 million saw happiness in having $18 million, and so on. This kind of thinking changes, of course, as people get more money, with happiness in reach at a level that is some multiple more than what they already have.

Although people predict that money strongly influences happiness, researchers also find that the actual relationship between wealth and happiness is more nuanced. In 2010 Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton analyzed data from over 450,000 responses to a daily survey of 1,000 U.S. residents by the Gallup Organization. They found that money does influence happiness at low to moderate levels of income. Real lack of money leads to more worry and sadness, higher levels of stress, less positive affect (happiness, enjoyment, and reports of smiling and laughter) and less favorable evaluations of one’s own life. Yet most of these effects only hold for people who earn $75,000 a year or less. Above about $75,000, higher income is not the simple ticket to happiness that we think it is.

Together, these studies show that we need far less money than we think to maximize our emotional well-being and minimize stress. This means that accumulating wealth isn’t about the pursuit of happiness—it’s about the pursuit of what we think (wrongly) will make us happy.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

When I voted this morning in the U.K. general election (at a polling station in a church) I realized that the choice of venue may impact electoral decisions. Most polling stations in my area are in either a community center or a church, which may have mental associations for voters (for example, church=conservative/right; community center=community/social responsibility/left). I was wondering if you have ever looked at this phenomenon.

—Zaur

Your intuition is absolutely right. In a 2008 paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Jonah Berger of the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and colleagues showed that Arizona voters assigned to vote in schools were more likely to support an education funding initiative. In a follow-up lab experiment, Mr. Berger also showed that even viewing images of schools makes people more supportive of tax increase to fund public schools.

In other words, the context for voting certainly changes how we look at the world and what decisions we make.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

People I meet sometimes ask me for my email address. On one hand, I want to keep in touch with those who are truly interested in friendship, but on the other, I don’t want to have a million meaningless exchanges. How can I get email only from people who are truly invested in real discussions?

—Ron

The problem is that email is too easy to send—it just takes a few seconds—while the person getting it on the other side might have to spend a lot of time responding to a particular message or to their email in general. My answer? Get a complex email address that takes some time to type. With this added effort you will get emails only from the people who are really interested in contacting you.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

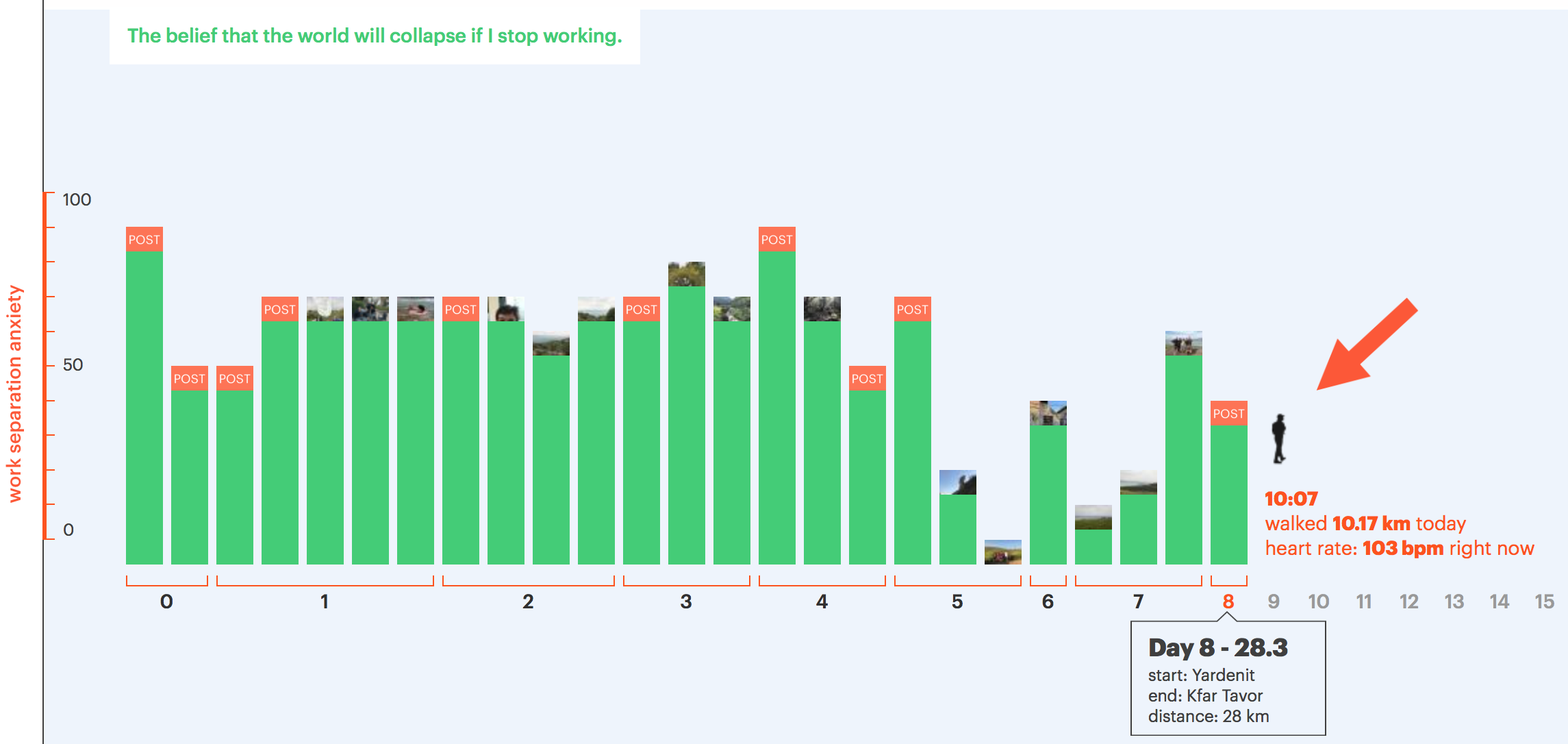

Hiking the Israel National Trail

I’m just starting the second week of my month-long hike, and have been tracking some things along the way:

- Light Happiness

- Deep Happiness

- Love

- Optimism

- Regret

- Empathy

- Loving Nature

- Work Separation Anxiety

- Communication Anxiety

So far, I appear to be pretty stable on most dimensions (light happiness has taken a few dips but deep happiness is consistently high, and love/optimism/loving nature have remained high), but I’m most noticeably experiencing a downward trend on work separation anxiety. The more time I spend hiking, the less I am worrying about the growing list of tasks that would otherwise keep me up at night. It took a few days for me to get here, but my work is now taking a back seat to the importance of this trip.

I decided to embark on this adventure as an acknowledgement of my upcoming 50th birthday, and as an opportunity to reflect on life and how I want to spend the rest of it.

You can follow my journey at http://danarielyishikingtheint.com and see how the next few weeks pan out!

Irrationally Yours,

Dan Ariely

Ask Ariely: On Momentary Meaning, Hurried Health, and Poetic Practice

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Why is it that the things that make me happy—such as watching basketball or going drinking—don’t give me a lasting feeling of contentment, while the things that feel deeply meaningful to me—such as my career or the book I’m writing—don’t give me much daily happiness? How should I divide my time between the things that make me happy and those that give me meaning?

—Vasini

Happiness comes in two varieties. The first is the simple type, when we get immediate pleasure from activities such as playing a sport, eating a good meal and so on. When you reflect on these things, you have no trouble telling yourself, “This was a good evening, and I’m happy.”

The second type of happiness is more complex and elusive. It comes from a feeling of fulfillment that might not be connected with daily happiness but is more lastingly gratifying. We experience it from such things as running a marathon, starting a new company, demonstrating for a righteous cause and so on.

Consider a marathon. An alien who arrived on Earth just in time to witness one might think, “These people are being tortured while everyone else watches. They must have done something terrible, and this is their punishment.” But we know better. Even if the individual moments of the race are painful, the overall experience can give people a more durable feeling of happiness, rooted in a sense of accomplishment, meaning and achievement.

The social psychologist Roy Baumeister and his colleagues distinguish between happiness and meaning. They see the first as satisfying our needs and wishes in the here-and-now, the latter as thinking beyond the present to express our deepest values and sense of self. Their research found, unsurprisingly, that pursuing meaning is often associated with increased stress and anxiety.

So be it. Simply pursuing the first type of happiness isn’t the way to live; we should aim to bring more of the second type of happiness into our lives, even if it won’t be as much fun every day.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently had my annual checkup, and my doctor spent maybe three minutes total with me during the visit. I know that physicians are busy, but are these quick visits the right way to go?

—James

Sadly, doctors increasingly feel pushed to move patients along as quickly as possible, like a production line. Research has shown that this approach hurts the doctor-patient relationship, which has important health implications.

Consider a 2014 study of patients who received electrical stimulation for chronic back pain, conducted by Jorge Fuentes of the University of Alberta and colleagues. They had medical professionals interact in one of two ways with their patients. Some were asked to keep their interactions short, while others were urged to ask deep questions, show empathy and speak supportively. Patients who received the rushed conversations reported higher levels of pain than those who got the deeper ones.

In other words, empathetic discussions are important for our health. Sadly, as physicians and other medical professionals become ever busier, we are shortchanging this vital part of healing.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Every year, my husband gets me a nice birthday card, but he never writes a personal note inside. Why?

—Ann

I suspect your husband overestimates the sentimental value of the words printed on the card, not realizing that they sound generic to you. Don’t judge him too harshly for this. Instead, buy one of those magnetic poetry sets and let him practice expressing himself on the fridge. Small steps.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Treating the Teacher, Perceiving Pain, and Realizing Resolutions

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I always agonize this time of year over getting the right gift for my children’s teachers. I hate gift certificates, which feel so thoughtless and generic. So what should I give?

—Raquel

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

As we enter December, I wonder whether I should make any New Year’s resolutions. I have been making them for years, and I inevitably fail to keep them, which is pretty frustrating. Should I give up or give it another go?

—Jamie

Don’t give up. Even if you stick to your resolution for, say, three or six months, you will be better off than you would have been if you had done nothing. And you might do better if you make New Year’s resolutions that are more limited and achievable. For example, what if instead of promising yourself that you will exercise three times a week for the whole year, you pledged just to work out for six weeks? That goal would be far easier to grasp, and maybe by the time you reach it, you will want to keep going.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like