Online Dating: Avoiding a bad Equilibrium

When going on a first date, we try to achieve a delicate balance between expressing ourselves, learning about the other person, but also not offending anyone — favoring friendly over controversial – even at the risk of sounding dull. This approach might be best exemplified by an amusing quote from the film Best in Show: “We have so much in common, we both love soup and snow peas, we love the outdoors, and talking and not talking. We could not talk or talk forever and still find things to not talk about.” Basically, in an attempt to coordinate on the right dating strategy, we stick to universally shared interests like food or the weather. It’s easy to talk about our views on mushroom and anchovies, and the topic arises easily over dinner at a pizzeria – still, that doesn’t guarantee a stimulating conversation, and certainly not a real measure of our long-term romantic match.

This is what economists call a bad equilibrium – it is a strategy that all the players in the game can adopt and converge on – but it is not a desirable outcome for anyone.

We decided to look at this problem in the context of online dating. We picked apart emails sent between online daters, prepared to dissect the juicy details of first introductions. And we found a general trend supporting the idea that people like to maintain boring equilibrium at all costs: we found a lot of people who may, in actuality, have interesting things to say, but presented themselves as utterly insipid in their written conversations. The dialogue was boring, consisting mainly of questions like, “Where did you go to college?” or “What are your hobbies?” “What is your line of work?” etc.

We sensed a compulsion to avoid rocking the boat, and so we decided to push these hesitant daters overboard. What did we do? We limited the type of discussions that online daters could engage in by eliminating their ability to ask anything that they wanted and giving them a preset list of questions and allowing them to ask only these questions. The questions we chose had nothing to do with the weather and how many brothers and sisters they have, and instead all the questions were interesting and personally revealing (ie., “how many romantic partners did you have?”, “When was your last breakup?”, “Do you have any STDs?”, “Have you ever broken someone’s heart?”, “How do you feel about abortion?”). Our daters had to choose questions from the list to ask another dater, and could not ask anything else. They were forced to risk it by posing questions that are considered outside of generally accepted bounds. And their partners responded, creating much livelier conversations than we had seen when daters came up with their own questions. Instead of talking about the World Cup or their favorite desserts, they shared their innermost fears or told the story of losing their virginity. Everyone, both sender and replier, was happier with the interaction.

What we learned from this little experiment is that when people are free to choose what type of discussions they want to have, they often gravitate toward an equilibrium that is easy to maintain but one that no one really enjoys or benefits from. The good news is that if we restrict the equilibria we can get people to gravitate toward behaviors that are better for everyone (more generally this suggests that some restricted marketplaces can yield more desirable outcomes).

And what can you do personally with this idea? Think about what you can do to make sure that your discussions are not the boring but not risky type. Maybe set the rules of discussion upfront and get your partner to agree that tonight you will only ask questions and talk about things you are truly interested in. Maybe you can agree to ask 5 difficult questions first, instead of wasting time talking about your favorite colors. Or maybe we can create a list of topics that are not allowed. By forcing people to step out of their comfort zone, risk tipping the relationship equilibria, we might ultimately gain more.

Sex and Smart Phones

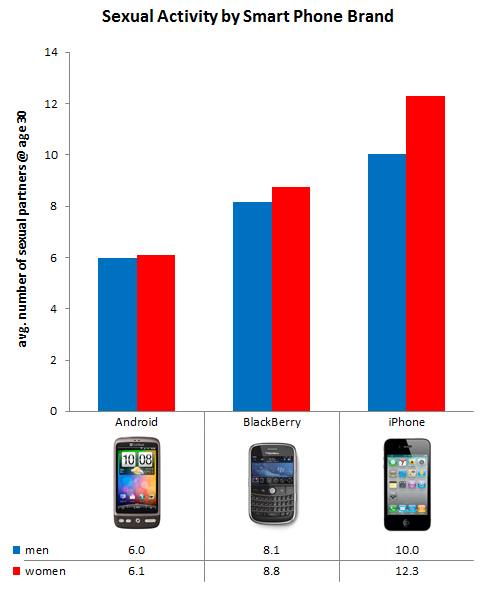

Popular online dating site OkCupid recently released some numbers users reported regarding their sex lives. One interesting correlation was between smart phone usage and number of sexual partners. As you see below, women iPhone users (at the age of 30) report having had 12.3 sexual partners, over twice as many as women Android users. Male smart phone users show a similar jump: from 6.0 sexual partners on Android to 10 on the iPhone. Blackberry users fall almost exactly in the middle.

The conclusion seems very simple: Look for a cute iPhone owner to get lucky with.

But, being careful about interpreting correlational data (and an avid iPhone user, I might add), I’ll offer a bit of advice: Please consider an alternative explanation of this graph: that iPhone owners might simply be more prone to exaggerate…..

Humans and the slime mould

One of the most general principles of human decision making is that we use relativity as a way to figure out how much we value things. We see a sale sign and the comparison of the current price to a more expensive past price makes us think that we are standing in front of a good deal. We see a modestly prices sweater next to a much more expensive one and we reason that is it a better deal for the money. And so on.

Relativity is not always the right strategy for figuring out how much to value things (very often it is not), but it gives us a quick and handy tool for going about the world making decisions.

Over the years the same type of relative decision making has been shown in monkeys, birds, and bees, but now it has been shown even with very simple lifeforms — the slime mould, Physarum polycephalum

Latty and Beekman did one such test using two food sources – one containing 3% oatmeal and covered in darkness (known as 3D), and another with 5% oatmeal that was brightly lit (5L). Bright light easily damages the slime mould, so it had to choose between a heftier but more irritating food source, and a smaller but more pleasant one. With no clear winner, it’s not surprising that the slime mould had no preference – it oozed towards each option just as often as the other.

But things changed when the researchers added a third option into the mix – a food source containing 1% oatmeal and shrouded in shadow (1D). This third alternative is clearly the inferior one, and the slime mould had little time for it. However, its presence changed the mould’s attitude toward the previous two options. Now, 80% of the slime mould headed towards the 3D source, while around 20% chose the brightly-lit 5L one. Even for slime mould relativity matters, suggesting that it is a very basic form of decision making!

Back to School #2

The Magic of Procrastination

Oscar Wilde once said, “I never put off till tomorrow what I can do the day after.” As a university professor, I constantly see Wilde’s words put into action. Each fall students arrive to the first day of class determined to meet deadlines and stay on top of their assignments. And each fall the human weakness to procrastinate gets the best of them. After a few years of witnessing this behavior, my colleague Klaus Wertenbroch and I worked up a few studies hoping to get to the root of this problem. Our guinea pigs were the delightful students in my class on consumer behavior.

As they settled into their chairs that first morning, I explained to them that they would have to submit three main papers over the 12-week semester and that these three papers would constitute a large part of their final grade. “And what are the deadlines?” asked one student. I smiled. “The deadlines are entirely up to you and you can hand in the papers any time before the end of the semester,” I replied. “But, by the end of this week, you must commit to a deadline for each paper. Once you set your deadlines, they can’t be changed. Late papers,” I added, “would be penalized at the rate of one percent off the grade for each day late.”

“But Professor Ariely,” asked another student, “given these instructions wouldn’t it make sense for us to select the last date possible?” “That’s an option,” I replied. “If you find that it makes sense, by all means do it.”

Now a perfectly rational student would set all the deadlines for the last day of class—after all, they could submit papers early, so why take a chance and select an earlier deadline than absolutely necessary? From this perspective, delaying the deadlines to the last day of he semester was clearly the best decision. But what if the students succumbed to temptation and procrastination? What if they knew that they are likely to fail? If the students were not rational and knew it, then they might set early deadlines and by doing so force themselves to start working on the projects earlier in the semester.

You would most likely predict that the students would succumb to procrastination (not a big surprise there)—but would they understand their own limitations and would they commit to earlier deadlines just to overcome their procrastination?

Interestingly, we found that the majority of students committed to earlier deadlines, and that this ability to commit resulted in higher grades. More generally, it seems that simply offering students a tool by which they could pre-commit publically to deadlines can help them achieve their goals.

How does this finding apply to non-students? When resolving to reach a goal—whether it is tackling a big project at work or saving for a vacation, it might help to first commit to a hard and clear deadline, and then inform our colleagues, friends, or spouse about it with the hope that this clear and public commitment will help keep us on track and ultimately fulfill our resolutions.

Back to School #1

The dark side of “Productivity Enhancing Tools”

Email, Facebook, and Twitter have greatly enhanced the ways we communicate. These handy modes of communication allow us to stay in touch with people all over the world without the restrictions of snail mail (too slow) or the telephone (is it too late/early to call?). As great as these communication tools are, they can also be major time-sinks. And even those of us who recognize their inefficiencies still fall into their trap. Why is this?

I think it has something to do with what the behavioral psychologist B. F. Skinner called “schedules of reinforcement.” Skinner used this phrase to describe the relationship between actions (in his case, a hungry rat pressing a lever in a so-called Skinner box) and their associated rewards (pellets of food). In particular, Skinner distinguished between fixed-ratio schedules of reinforcement and variable-ratio schedules of reinforcement. Under a fixed schedule, a rat received a reward of food after it pressed the lever a fixed number of times—say 100 times. Under the variable schedule, the rat earned the food pellet after it pressed the lever a random number of times. Sometimes it would receive the food after pressing 10 times, and sometimes after pressing 200 times.

Thus, under the variable schedule of reinforcement, the arrival of the reward is unpredictable. On the face of it, one might expect that the fixed schedules of reinforcement would be more motivating and rewarding because the rat can learn to predict the outcome of his work. Instead, Skinner found that the variable schedules were actually more motivating. The most telling result was that when the rewards ceased, the rats that were under the fixed schedules stopped working almost immediately, but those under the variable schedules kept working for a very long time.

So, what do food pellets have to do with e-mail? If you think about it, e-mail is very much like trying to get the pellet rewards. Most of it is junk and the equivalent to pulling the lever and getting nothing in return, but every so often we receive a message that we really want. Maybe it contains good news about a job, a bit of gossip, a note from someone we haven’t heard from in a long time, or some important piece of information. We are so happy to receive the unexpected e-mail (pellet) that we become addicted to checking, hoping for more such surprises. We just keep pressing that lever, over and over again, until we get our reward.

This explanation gives me a better understanding of my own e-mail addiction, and more important, it might suggest a few means of escape from this Skinner box and its variable schedule of reinforcement. One helpful approach I’ve discovered is to turn off the automatic e-mail-checking feature. This action doesn’t eliminate my checking email too often, but it reduces the frequency with which my computer notifies me that I have new e-mail waiting (some of it, I would think to myself, must be interesting, urgent, or relevant). Another way I am trying to wean myself from continuously checking email (a tendency that only got worse for me when I got an iPhone), is by only checking email during specific blocks of time. If we understand the hold that a random schedule of reinforcement has on our email behavior, maybe, just maybe we can outsmart our own nature.

Even Skinner had a trick to counterbalance daily distractions: As soon as he arrived at his office, he would write 800 words on whatever research project he happened to be working on—and he did this before doing anything else. Granted, 800 words is not a lot in the scheme of things but if you think about writing 800 words each day you would realize how this small output can add up over time. I am also quite certain that if Skinner had email he would similarly not have checked it before putting in a few hours of productive work. Now if we could only learn something from one of the world’s experts on learning….

Procrastination and self control

Pain decreases pain

In Chapter 6 of “The Upside of Irrationality” I wrote about the the process of adaptation, which is the process by which we get used to stuff — like pain, romantic partners, and new cars.

Some of the personal experiences and experiments I described were about how experiencing pain when I was hospitalized caused me (and others) to view pain differently and with a lower intensity.

A new study on back pain, showed the basic same results:

“This study of 396 adults with chronic back pain found that those with some lifetime adversity reported less physical impairment, disability, and heavy utilization of health care than those who had experienced either no adversity or a high level of adversity…… The data suggest that adversity-exposure also may protect against psychiatric disturbances that occur with chronic back pain…”

I am not suggesting that everyone goes and get some more experience in adversity — just to prepare ourselves in case something bad will take place in the future. But, it is interesting to realize that negative experiences influence our adaptation, and this way also on our ability to deal more positively with new negative circumstances.

Dan

The password conundrum

By Alon Nir

0. Intro

Sometimes interesting opportunities can emerge from unfavorable situations. Tense diplomatic atmosphere between Israel and Turkey in the past couple of months, brought on a cyber-attack from the Turkish side. A major Israeli apartment-listing website was hacked and so was Pizza Hut’s local website. The credentials of over 100,000 user accounts (roughly 2% of internet users in the country) were revealed and published on dubious Turkish forums. Naturally, it wasn’t long before these lucrative spreadsheets, containing usernames, email addresses and passwords became so widespread anyone with basic googling abilities could find them. One person who got his hands on these files comes from a profession no less defamed than computer-hacking. You guessed it – an economist. Me.

I took a look at the spreadsheets and after some basic analysis I was left with a few interesting insights. The data reveal the extent to which people fail to think creatively and incorporate even a touch of randomness in their username and password selection.

1. Popular Passwords

My analysis focused on a spreadsheet containing 31,588 users of the above mentioned apartment-listing website. The reason I chose it is because that website was (evidently) particularly lenient in the registration process and didn’t even strict choices of password. One digit password? Not a problem. This leniency probably isn’t the best security policy the website could adopt, but it is valuable for our analysis as it shows what people will do when they are unconstrained.

15,820 of these 31,588 registered users (slightly over 50%!) used their email address as their username. Furthermore, 675 people (over 2%) picked their phone number as a username. Both of these choices aren’t considered very secure, since phone numbers, and email addresses in particular, are easy to find out.

While these two bits of information give an indication on lack of creativity on the users’ part, the really interesting discovery is their selection of passwords.

The most common password was 123456 (584 users), with 1234 as the runner up (569) and 12345 coming in third (388). All in all, 1786 passwords (5.65%!) were comprised of consecutive increasing numerals. This means that one person in 18 didn’t muster the cognitive capacity to generate a password more intricate than 1234 and the like.

788 people (roughly 2.5%, or one in forty people) chose a password identical to their username.

417 people (1.32%) chose a password comprised of identical digits (e.g. 1111).

Keyboard patterns were ubiquitous, horizontal in particular: on top of the 1786 ‘123X’ passwords mentioned above, 123 passwords began with ‘qwe’ (including 25 instances of ‘qwerty’), 41 with ‘asd’, and 31 with ‘zxc’. It’s interesting to see how the frequency of these patterns falls as we go to a lower line on the keyboard. A similar distribution appears when looking at vertical lines on the keyboard, though the frequency is substantially lower (‘1qaz’ and ‘qaz’ make up 83 observations combined).

48 passwords began with ‘abc’ (e.g. ‘abcdef’, ‘abc123’, etc.).

And finally, 69 passwords had variants of the actual word ‘password’, with no less than 29 exact matches.

What’s more interesting is the fact that using this information, diligent mischiefs hacked into tens of thousands of email and Facebook accounts, which indicates that a high percentage of the people in our sample uses the same (trivial) password for different websites. It also refutes arguments that people carelessly entered an easy password because they didn’t care much for their account on that particular website.

Lastly, I looked at the spreadsheet with Pizza Hut’s users credentials hoping something will catch my eye and help me gain a better insight into password selection. I didn’t have to look for long, as roughly 200 people (out of around 70K accounts, I must mention) chose ‘pizza’ or something similar as password. This got me thinking, and I suspect that password selection might be influenced by cognitive availability. I went back to the original data and found that 89 had the name of the website as part of their password. Other passwords (though much more rare) were nouns like ‘coffee’ and brand names like ‘samsung’, ‘acer’, ‘cocacola’, ‘nokia’ and others, all of which can be attributed to physical objects just in front of the user’s eyes or in his hand. Add this to the 2,000 or so patterned passwords I mentioned earlier (visual availability on the keyboard), and you get a plausible explanation in my view.

2. Explaining the Findings

So what can account for this password picking behavior? A few possible explanations come to mind. Let me describe them by using John, an imaginary typical internet user, as an example.

One explanation is that when John first embarks on setting up a new account at a website, he knows he’ll get a blank profile when the registration process is done. Since his profile will contain no information, the ‘price’ (in terms of lost information, contacts, time, etc.) John will pay in case that an amicable hacker takes over his account is close to zero. Hence, he is reluctant to strain himself making up, and remembering, a truly unique password.

The problem starts a while later, when John’s email box is already full with valuable correspondences, and his Facebook page is populated with hundreds of friends (including a few flirtatious Janes). Then, a more difficult to decipher password is of true value, but John irrationally sticks to the password he already has. It can be because he’s a terrible procrastinator, forgetful, or even due to the Sunk Cost bias – in his mind John already “paid” the price (in terms of mental resources and time spent) for setting a password, and that’s why he refrains from going through the process again. As time passes the incentive to change password becomes greater and greater, but try telling that to John.

3. Conclusion

When I first put my hands on the coveted files, I did not expect to find such interest in password selection, but the more I go over the data, and the more I think about it, I see the value of studying the way people choose passwords. As you see from the above analysis, it’s an example of a decision making problem where behavioral and cognitive processes, and biases, come into play. Since it’s a one-shot game and the decision is kept in strict confidentiality (until, of course, someone picks up on security breaches), the setting is rather simplified and the observed behavior is of research value. In a way, we have here a form of a natural experiment; it’s just unfortunate the way the data were obtained.

If you have any other theories explaining password selection, please feel free to share them in the comments below. Don’t worry, no registration is required ….

An interview with Miguel Barbosa

A few days ago I had a fun interview with Miguel Barbosa. Miguel just posted the interview on his blog.

Here is one sample question and answer:

Miguel: You touched on my next question which relates to your chapter on meaning. Tell us about your findings on the importance of meaning in the workplace. What’s your advice for people trying to attach meaning to their jobs?

Dan: I think it’s very hard to have meaning if you are working for someone and don’t have much autonomy. But the upside is that with a little work we can create work environments that provide people with autonomy and are more likely to lead to feelings of meaningful work. Let me tell you a story that happened to me three weeks ago.

Three weeks ago I was in Seattle where an ex-student of mine who works for a big software company. She contacted me six weeks prior and I agreed to meet with her team. Something happened at that company in the weeks before I gave the talk. The background being that my student and a small team of people had discovered an idea which they thought was the best innovation in the “computer world.” They worked very hard on this idea for two years and the CEO of the company looked at it and said I’m canceling the project.

So here I was sitting with a group of highly creative people, who were completely deflated- In my life I’ve never seen anyone (in the high-tech industry) with a lower level of motivation. So I asked them, “How many of you show up to work on time since the project has been shut down?” Nobody raised their hand. I asked them, “How many of you go home early?” Everyone raised their hand. Lastly, I asked them, “How many of you feel that you should have taken the opportunity to fudge on your expense reports?” In this case, no one answered the question — rather everyone sat laughing to themselves—in a way that makes me think that they would have fudged their expense reports. So here you have a case of people who worked incredibly hard on a project and basically got rejected. Which leads me to ask how could the CEO have behaved differently if he was also trying to create a more positive feelings for the team members. So I posed this question to the team and they came up with different answers:

1. They said senior management could have allowed the team to present the project to the entire company.

2. Management could have gone a step further and allowed the team to build a prototype.

3. Management could have taken the time to understand the technology and see the possibilities of applying it to other areas of the firm or product development.

4. They could have asked the team to write about the process of developing the idea.

So there are many approaches senior management could have taken to boost the morale of the research team. But the key is that most ideas for boosting morale require a significant amount of time. If you think of people as rats working in a maze that then there is no reason to help their motivations or explain why you said “No!”. But if you think of people as driven by internal motivation then you want to worry about internal motivation then you might want to spend some time and effort increasing internal motivation. That is something the executive did not do, and I suspect that because of this the research team will eventually dissolve.

If you want to read more, here is a link to Miguel’s blog

How we view people with medical labels?

A few weeks ago we conducted an online study on this question (the link to the survey was the “Click to participate” on the right side of the screen), and I wanted to thank the participants and tell you a bit about what we found.

In this study all the participants viewed a potentially funny video involving an individual who would seem to have “issues.” (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Sd-j0rKeKw) The video clip showed a college student getting upset in an arguably overdramatic fashion after she got in trouble for inadvertently setting off her sorority house’s fire alarm by using the house’s fire extinguisher just for fun. Her friend apparently found it amusing enough to post it on youtube, and the clip has received millions of views since then.

The study had three groups: The first one was not given any additional information regarding the person. A second group was told that this person had suffered from stress since childhood. The third group were told that the person student in the clip had suffered from OCD since childhood.

What we found was that participants who were told that the girl had suffered from OCD since childhood found the clip less funny, laughed out loud from it less, and were less likely to recommend it to others than other participants. They also felt worse for the student and thought she deserved a smaller fine for inadvertently setting off the sorority house’s fire alarm than if they were either told beforehand that the student had suffered from stress since childhood (or received no justification at all). Participants who were told she had OCD also thought she seemed more likeable, intelligent, and creative. But they also thought that she seemed like a bigger loner and more antisocial.

What I think this means (and we need more research on this) is that giving individuals a disorder-label causes others viewing them to place the blame on the disorder and not on the person. Think for example about a parent who is told that their kid has ADHD – would this parent blame themselves less than if they were told that their kid is an active difficult kid? I think the answer is yes, and maybe this is one of the reasons that we as a society seem to be obsessed with diagnostic labels (other reasons include incentives for psychologists, medical companies etc).

By the way, did I tell you that I have a Restless Hand Syndrome”?

Irrationally yours

Dan

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like