Ask Ariely: On Denying Donuts, Car Conversations, and Curbing Confidence

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I often fight with temptation, and it usually wins. I want to eat better, exercise more, save a bit for retirement and in general consider the future when I make decisions. How can I resist temptation?

—John

There’s no easy answer to this old problem. As Oscar Wilde famously said, “I can resist anything except temptation.” The endless stream of enticements throughout the day makes it hard to consistently make good decisions. Even if we resist an urge here and there, we tend to end up failing a lot.

That’s where personal rules can help. In effect, we make a one-time decision when we create a guideline, and from then on, we are just executing a pre-existing policy, which makes life considerably simpler.

Imagine that someone in your office brought in a box of doughnuts every day, forcing you to decide every day whether to indulge. You would probably be able to overcome the temptation from time to time, but you would also probably break down on other occasions. If you simply had a flat personal policy—no doughnuts during the workweek—you would bypass the daily decision.

Of course, even the strongest among us is likely to break such rules every now and then, but having a policy and declaring it to yourself will help to keep you from giving in.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Studies have shown that talking on a cellphone while driving (even using hands-free technology) is about as dangerous as driving while intoxicated. But talking to someone sitting in the passenger seat is widely considered fine. Why is talking on the phone in the car so much more dangerous?

—Larry

Your question revolves around the social norms of conversation. When we drive, a passenger can see what’s going on around the car—a bus swerving, a pedestrian running across the street, a light turning amber—and with this shared knowledge, both the driver and the passenger adjust the conversation. They chat more intensely when the driving conditions are good, and they shut up when road conditions demand more attention. A pause in the conversation isn’t strange for the passenger, who can also see what’s going on.

By contrast, when we’re talking on the phone while driving, our interlocutor has no idea what’s happening in and around the car and keeps up the conversation whether we can afford to divide our attention or not. The driver, who feels social pressure to be polite and keep chatting, has less attention to devote to the road and winds up taking extra chances. We thus put ourselves at great personal risk just to avoid being rude.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I work at a consulting company where a heavy dose of personal overconfidence is standard. Any advice on how to reduce it?

—Jeff

I’m not sure this is a problem. Social progress often depends on overly confident people. Consider those who open restaurants: They are clearly fighting the odds, and if they looked objectively at their decision, they might not be ready to gamble. But would we want to live in a society where people avoid such risks? The food would certainly be worse.

Overconfidence has an upside as well as a downside. So before you try to decrease it, think about the benefits it brings to your firm—including more innovation and motivation—and only then decide whether decreasing overconfidence is really the way to go.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Helping Hands, Popular Posts, and Mischievous Motivators

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m struggling financially, and I’m considering asking some friends for help—perhaps seeing if they could offer a small amount every month until things get better. Is this a good strategy, or should I ask for more money upfront?

—Jordan

Mixing finances and personal relationships is always risky. But if you have the right friends—understanding, compassionate and generous of spirit—and are determined to go this route, I would ask them for all the money upfront.

The issue here isn’t just asking them for help; it is their having to think about your request. When a friendship gets tangled up with personal finances, the best you can hope for is that all involved won’t have it in mind when they spend time together and will be able just to enjoy one another’s company. But if you have to keep asking your friends for more installments, everyone is more likely to be thinking about it. That will lead to more uncomfortable conversations, strain the friendships and add to your financial stress.

So the simplest route is to ask just once, for the full amount that you need, thank your friends sincerely—and not mention it again until you can pay them back.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Why would people rather believe a viral social-media post over credible scientific information?

—Efrat

Because we are cognitively lazy and want simple answers.

A fuller explanation would also concede that academics and scientists bear some responsibility for the difficulty that some feel in taking our research at face value. We tend to write in technical jargon, to add endless qualifications to our findings and to insist that every topic needs to be studied further—all of which makes it hard for nonspecialists to take guidance from us.

As for posts on social media, their believability has to do with what psychologists call “social proof.” That is, we instinctively follow the herd, without realizing that we are doing it. The algorithms that social networks use are designed to exploit social proof and to get people to spend more time online. When a post becomes popular, the social networks promote it even more heavily, targeting users who are likely to be sympathetic, with the goal of maximizing their use of the network. Of course, that means that more people will see the popular post, pushing the chance of something going viral even higher.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My son, a fourth-grader, recently had another child’s progress report placed in his box by accident. That made me wonder: If children were “accidentally” sent a fake report card, along with their own, for another kid who was making slightly better progress in school, would it motivate them to work harder?

—Paula

I like the way you think—slightly devious but very creative. You’re also right. Giving people (children included) the sense that another person is doing better increases their motivation—so long as it’s only slightly better. Setting unattainable goals doesn’t work well, but offering a reachable one can be a useful goad.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Interrupting the Internet, Involving Ideologies, and Admiring Air Travel

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

We try to set boundaries on phone and computer use by our teenagers, who are supposed to stop using their devices by 9 p.m. But my husband stays on his phone long after that, researching vacations or kitchen appliances—which, to my mind, is a clear double standard. Am I right?

—Tina

I’m with you: Setting a bad personal example isn’t a great way to encourage good behavior in your teens. I would pressure your husband to be a better role model.

Or you could just turn off the Wi-Fi router after 9 p.m., which would guarantee that nobody could go online. It is hard to resist temptation when giving in is so easy—in this case, when the internet is just a click away. By creating roadblocks, even small ones like turning a router back on, we can create a natural pause for reflection that should encourage better decisions.

The only downside is that, with all the free time your husband will now have, he might want to spend it with you. Are you ready for this?

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

How can some people see global warming as a huge crisis facing humanity while others dismiss it as a big red herring? Why do Republicans and Democrats reach such different conclusions reading the same data? Can ideologies really lead to such strong biases in the way that we look at the world?

—Rachel

Ideology can easily color our views, even on scientific data. In much the same way that Israelis and Palestinians can see the same clash and place the blame entirely differently, so too can political ideology taint almost everything we experience. And, of course, people with different ideologies don’t read the same information: We largely pick the information outlets that support our initial beliefs, making it even easier to become convinced that we are correct.

This sort of biased interpretation of data isn’t the end of it, though. As Troy Campbell and Aaron Kay showed in a 2014 paper in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, “an aversion to the solutions associated with the problem” can color our view of the problem itself.

When the researchers exposed participants to solutions to global warming based on more government regulation, those who supported free-market ideologies were much less likely to acknowledge the hazards of climate change. On the other hand, when the researchers proposed solutions based on less government regulation and more autonomy for private enterprise, these same participants were much more likely to see the dangers of global warming.

That suggests one way forward: Don’t just shove more data in peoples’ faces and ask them why they won’t face up to reality, but work on solutions that align with a wide variety of ideologies.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I fly a lot for work, and my annoyance with air travel is rising all the time. These days, I get upset the night before a flight just from knowing I have to head for the airport the next day. What can I do to reduce my distaste for flying?

—David

Learn more about the physics of flying and the complexity of the operational side of managing a large airline. We are quick to take things for granted. We get wondrous new technologies such as Google and quickly stop being impressed; we get clean, running water in our homes and stop being amazed. By reminding yourself every time you get to an airport about the marvels of flight and the difficulty of running a big transportation company, you will focus on the full experience—and enjoy it much more.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

How Does Pocket Ariely Make Sense of Life?

Check it out at: http://danariely.com/pocket-ariely/

Have you ever been in a situation where you could really use my help? How about putting away that last cupcake? Or saving that extra dollar for retirement? Maybe getting things done at work without draining all your time and energy? Or, maybe, you just need to spend less time giving out likes and more time nourishing your brain with food for thought?

I know I’ve felt that way, and chances are… so have you.

I want to introduce you to Pocket Ariely, a digital library of my most relevant work in behavioral economics and the best cheat sheet to life’s most difficult issues in Finance, Health, Productivity, Morality, Romance, and so much more. With Pocket Ariely, you can access videos, podcasts, articles, and even games that will prepare you to make sense of life through social science insights.

What’s more, all profits from Pocket Ariely will be put toward the research being conducted at my lab, the Center for Advanced Hindsight at Duke University. With your help, we will continue to advance the blossoming field of behavioral economics and continue the process of showing the world how irrational humans can be (sometimes), and ways to fix it.

The app is not free, but think about the monthly (weekly? daily?) $5 you spend on a Venti Caramel Macchiato at Starbucks, and skip one every other month in the name of science (your waistline will thank you too!). I promise you that we will keep working hard on some of humanity’s most pressing issues all for the cost of the occasional cup of Joe. Not a bad deal huh?

Download Pocket Ariely now

from the App Store and Google Play Store.

Irrationally yours,

Dan

Ask Ariely: On Coin Conundrums, Reading Realizations, and Ice-Breaking Ideas

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

A chain of coffee shops in Israel, where I live, had tremendous success charging a flat price of five shekels (about $1.35) for coffee and other items on its menu. People would get coffee and often a muffin or something else to eat. Now the chain has raised the flat price at its cafes to six shekels, and suddenly my friends don’t go anymore. Why?

—Ron

Some time ago, Unilever entered several markets in India and Africa, offering tiny amounts of products such as soap or milk in packages that were small and inexpensive. The company found that it could do well selling these products so long as the price for them matched the smallest coin then circulating in the economy

For example, as long as people in Kenya were buying a small portion of milk for 10 shillings, they would purchase a lot of it. But when the cost increased even a smidgen over the value of the smallest local coin, sales dropped dramatically.

I suspect that your coffee shop is suffering for the same reason. In Israel, the five-shekel coin is widely used, and though Israel has smaller coins, the same general principle probably applies: People are more inclined to buy items that are priced on the scale of familiar, low-denomination coins.

When something costs the same as a coin, we can categorize the purchase as cheap and not think too much about it. But the moment something costs more than a single coin, we start thinking more carefully about whether or not we want to buy it.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I turned 40 this year, and it is harder and harder for me to read text on my cellphone. Why did cellphone companies start reducing the font sizes on our phones?

—Ayelet

It’s clearly a conspiracy among evil conglomerates. The cellphone companies are joining forces with the eyeglasses companies to persuade those of us over 40 that our eyesight is deteriorating and we need to purchase buy new glasses.

On the other hand, it may be that sometimes we just don’t want to acknowledge certain conclusions or get certain answers (that we are spending more than we should, that we are getting older and so on). In such cases, people turn out to have a startling ability for self-delusion, even when the desire not to acknowledge the truth in the short term can hurt us in the long term.

So maybe you should try to adopt eyeglasses as a fashion statement and use them to express your new, somewhat older and increasingly excellent self. (And happy birthday!)

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m going to host a party soon with some old and new friends, and I want to do something to break the ice. Any advice?

—Moran

In such situations, I find it very useful to start the evening by declaring that the event will operate under Las Vegas rules: What happens at the party stays at the party. Next I tell people that sharing embarrassing stories is a wonderful way to get to know one another. Finally, I get things going by sharing one about myself.

To give you the feel for it, here is the shortest such story anyone has ever shared with me: “I’m going on a blind date. I knock on the door. A woman opens it. I ask, ‘Is your daughter home?’ The door closes. I turn around and leave.”

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Financial Feelings, Polling Places, and Meaningless Messages

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Why is society structured around the accumulation of wealth? Is this part of human nature, and is it the best way to achieve happiness?

—Annie

Most of us believe that more money brings more happiness—and the wealthy are no exception. In a 2014 survey of very wealthy clients at a large investment bank, Mike Norton of Harvard Business School asked clients how happy they were and how much money would make them really happy.

Regardless of the amount they already had, they responded that they’d need about three times more to feel happy. So people with $2 million thought they could achieve happiness if they had $6 million, while those with $6 million saw happiness in having $18 million, and so on. This kind of thinking changes, of course, as people get more money, with happiness in reach at a level that is some multiple more than what they already have.

Although people predict that money strongly influences happiness, researchers also find that the actual relationship between wealth and happiness is more nuanced. In 2010 Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton analyzed data from over 450,000 responses to a daily survey of 1,000 U.S. residents by the Gallup Organization. They found that money does influence happiness at low to moderate levels of income. Real lack of money leads to more worry and sadness, higher levels of stress, less positive affect (happiness, enjoyment, and reports of smiling and laughter) and less favorable evaluations of one’s own life. Yet most of these effects only hold for people who earn $75,000 a year or less. Above about $75,000, higher income is not the simple ticket to happiness that we think it is.

Together, these studies show that we need far less money than we think to maximize our emotional well-being and minimize stress. This means that accumulating wealth isn’t about the pursuit of happiness—it’s about the pursuit of what we think (wrongly) will make us happy.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

When I voted this morning in the U.K. general election (at a polling station in a church) I realized that the choice of venue may impact electoral decisions. Most polling stations in my area are in either a community center or a church, which may have mental associations for voters (for example, church=conservative/right; community center=community/social responsibility/left). I was wondering if you have ever looked at this phenomenon.

—Zaur

Your intuition is absolutely right. In a 2008 paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Jonah Berger of the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and colleagues showed that Arizona voters assigned to vote in schools were more likely to support an education funding initiative. In a follow-up lab experiment, Mr. Berger also showed that even viewing images of schools makes people more supportive of tax increase to fund public schools.

In other words, the context for voting certainly changes how we look at the world and what decisions we make.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

People I meet sometimes ask me for my email address. On one hand, I want to keep in touch with those who are truly interested in friendship, but on the other, I don’t want to have a million meaningless exchanges. How can I get email only from people who are truly invested in real discussions?

—Ron

The problem is that email is too easy to send—it just takes a few seconds—while the person getting it on the other side might have to spend a lot of time responding to a particular message or to their email in general. My answer? Get a complex email address that takes some time to type. With this added effort you will get emails only from the people who are really interested in contacting you.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

Beginning at the End

Part of the CAH Startup Lab Experimenting in Business Series

By Rachael Meleney and Aline Holzwarth

Missteps in business are costly—they drain time, energy, and money. Of course, business leaders never start a project with the intention to fail—whether it’s implementing a new program, launching a new technology, or trying a new marketing campaign. Yet, new ventures are at risk of floundering if not properly approached—that is, making evidence-based decisions rather than relying on intuition.

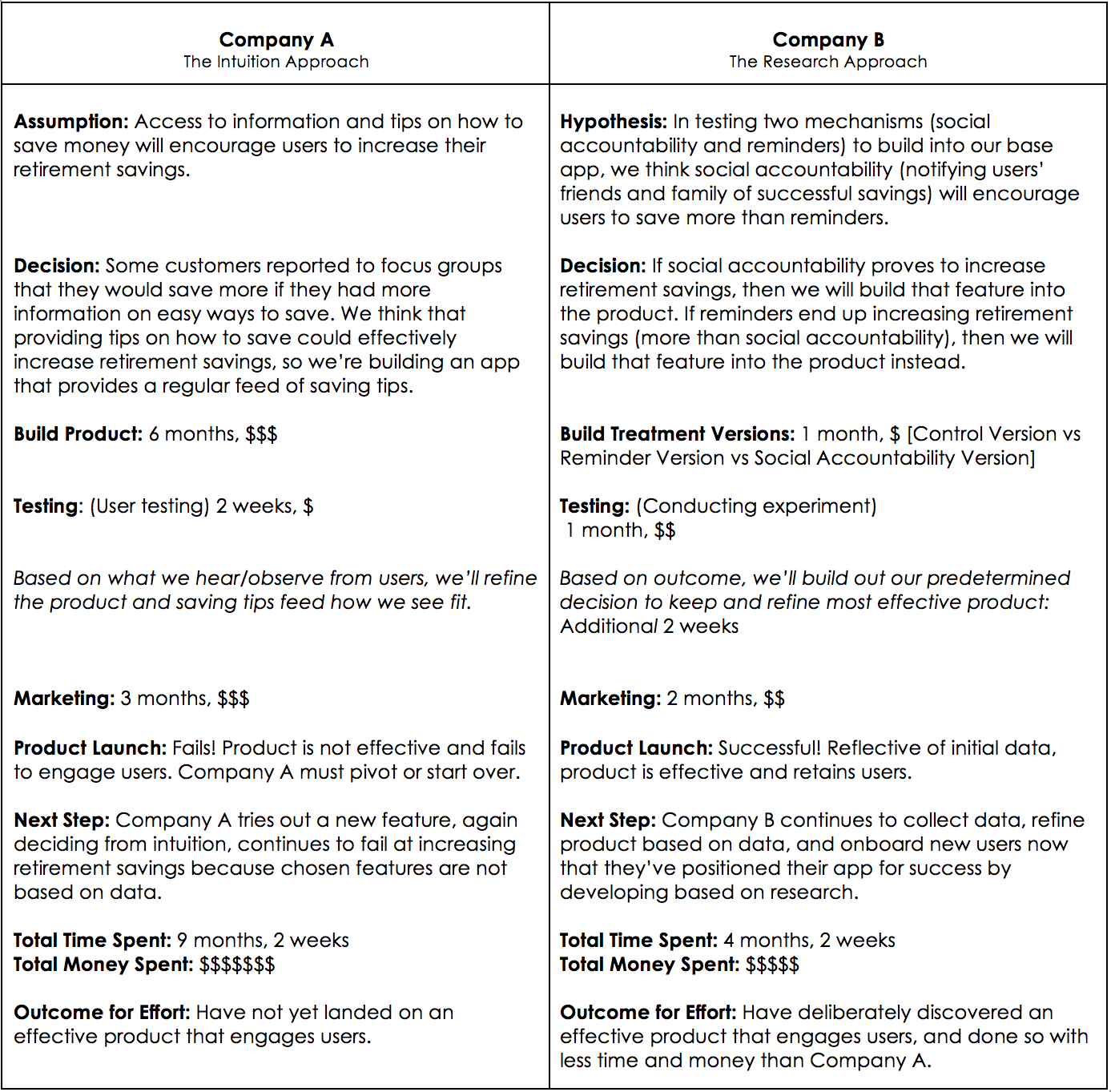

Let’s say your company is in the business of connecting consumers to savings accounts, helping them save for retirement through your app. You need to decide how your product will achieve this. Let’s look at how an intuition-backed approach (Company A) compares to a research-backed approach (Company B) in this scenario:

What if there was a way to more reliably ensure that business risks weren’t as prone to failure? As we see in the example above, the solution lies in well-planned experimentation.

If businesses can learn to identify concrete decisions needed to move new or existing projects forward, and set up experiments that directly inform those decisions, then much of the painful time, energy, and monetary costs of mistakes can be avoided. However, many business leaders and entrepreneurs are weary and unsure about how to leverage research to benefit their companies most effectively. Therefore, they rely (perhaps unknowingly) on riskier decision-making approaches.

As social scientists at Dan Ariely’s Center for Advanced Hindsight at Duke University, we’re in the business of human behavior and decision-making. We see in our research the effects that our biases and environments have on our ability to make optimal decisions. In the high-risk environment of building a company, founders aren’t well-served by calling shots based on gut feelings or reasoning plagued by cognitive biases. (Don’t feel bad! We’re only human!)

The better route? Rigorous experimentation. Asking well-formed research questions, designing tests with isolated variables and control groups, randomizing users to groups, and using data to inform business decisions.

Adapting the Process: Making Experimental Results Actionable

At the Center for Advanced Hindsight’s Startup Lab (our academic incubator for health and finance technologies), our mission is to equip startups with the tools to make business decisions firmly grounded in research.

But the research process has to be more accessible to businesses. Entrepreneurs often come to us excited about research, but with little to no idea of what it takes to execute a rigorous experiment. There’s a lot of anguish, confusion, and hesitation about where to even begin.

The Startup Lab makes experimentation more approachable to entrepreneurs who have the will, but often not the time and resources to run studies like our colleagues in academia.

There are specific considerations that businesses take into account when wading into the world of research. An important one is what makes investing in experimentation worthwhile? The driving purpose of running experiments, in most business contexts, is to uncover results that are clearly actionable.

So how do you ensure actionable results? You set up your process with this goal in mind from the start – not as an afterthought. The Startup Lab adapts Alan R. Andreasen’s concept of “backward market research”[1] to bring the process of planning and executing a research project to entrepreneurs.

The ‘Backward’ Approach: Beginning at the End

“Beginning at the end” means that you determine what decision you’ll make when you know the results of your research, first, and let that dictate what data you need to collect and what your results need to look like in order to make that decision.

This ‘backward’ planning is not how businesses usually approach research projects. The typical approach to research is to start with a problem. In business, this often leads to identifying a lot of vague unknowns—a “broad area of ignorance” as Andreasen calls it—and leaves a loosely defined goal of simply reducing ignorance. For example, startups often come to us with the goal of better understanding their customers. While we commend this noble goal, we ask, “to what end?”

What business decision will you make based on what your research uncovers?

The problem with the simple exploratory approach is that it sets you up for certain failure from the start. An unclear question produces an unclear answer. You’ll end up with data that you can’t possibly base a concrete decision on.

Let’s revisit the example of Company A (the intuition-based entrepreneurs) and Company B (their ‘backward market research’ counterparts). If you approach product development based on intuition like Company A, then you may be tempted to ask your customers about the challenges they have saving, or their ideal income at retirement – but this would be misguided if you don’t first determine what you will do with this information. If you find that your customers have trouble saving, you might conclude that you need to give them more information about the benefits of saving for retirement. If you create and implement this content into your app only to discover that it is completely ineffective at increasing savings, will you trash your product and start over? (Probably not. But if you set up your research in this way, then that may be the only logical conclusion.)

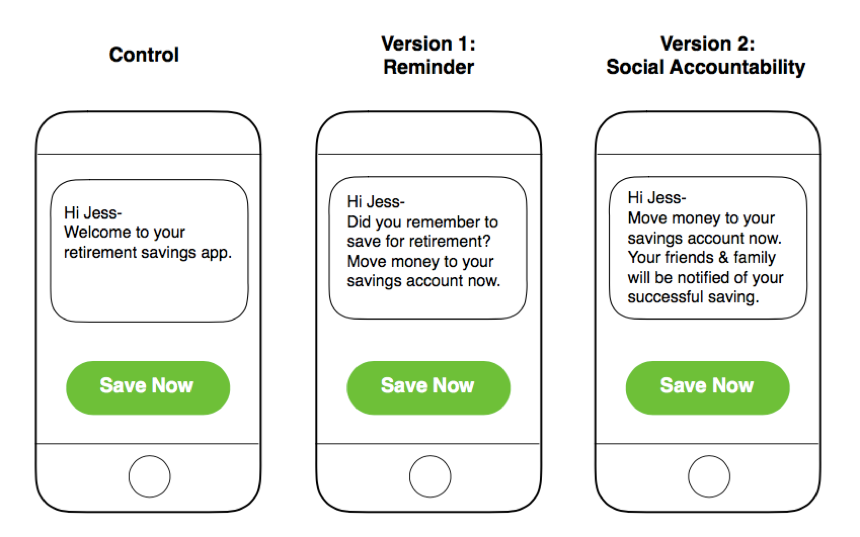

But imagine that instead, like Company B, you plan a research project to collect data on your users’ saving behavior (instead of probing to reduce your ignorance on their stated savings challenges). You set up an experiment to test two different ways of encouraging users to save (your two treatment groups, reminders and social accountability) against the current version of your product (what we call a control group).

Now you’ve set up an experiment, but you can’t stop at designing your research.

The “backward market research” approach forces you to specify which decisions you will make based on the outcome.

If the social accountability version leads your users to save twice as much as they do when using your base product, will you implement this mechanism in your product strategy? How will you do so, and what might the implications be? Once you determine 1.) The decision you will make from every possible outcome of your research results and 2.) How each decision will be implemented, then your research is set up to lead to actionable insights that have the power to move your business forward.

P.S. You too can design and conduct experiments using the ‘backward market research’ method. Use our handy tool to guide you through the backward approach: ‘Beginning at the End’ Worksheet.

And remember, to orient your research toward actionable decisions, start with the end in mind.

[1] Andreasen, A. R. (1985). ‘Backward’Market Research. Harvard Business Review, 63(3), 176-182.

At the Center for Advanced Hindsight’s Startup Lab, our academic incubator for health and finance tech solutions, we aim to instill a commitment to research-backed business decisions in the companies we bring into our fold. We will be releasing more articles and tools like this as part of our Experimenting in Business Series on our blog. Leveraging research for smart business decisions is a powerful skill—we’re aiming to make rigorous experimenting less intimidating and more accessible to a broad range of businesses.

By the way—we’re also accepting applications for the Startup Lab’s upcoming program, which starts in October. We’re looking for startups that are eager to experiment, and demonstrate a passion for building research-backed solutions to health and finance challenges.

APPLY NOW.

You only have until June 30th at 5pm EST.

Ask Ariely: On Surveillance Success, Relationship Recovery, and Taste Temptation

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m seeing many more surveillance cameras in shopping malls, restaurants, roads and even my workplace. I doubt that anyone is watching all these acres of footage, so why should anyone care about being recorded? Won’t the cameras’ ubiquity undermine their effectiveness?

—Bruce

Don’t be so sure. Even if no one is watching the cameras’ video in real time, authorities can still use it after a crime has occurred to figure out who did what to whom. So please don’t start behaving badly just because you’re seeing so many cameras around.

Moreover, from a psychological perspective, surveillance cameras also provide a good mechanism for reminding us about morality. One of the most powerful motivators of honest behavior is our own moral self-evaluations (known to experts as “self-concept maintenance”). When we have other people (or cameras) around, they remind us about the people we want to be, which spurs us to behave more nobly.

An early demonstration of this principle came from research in 1976 by Edward Diener and Mark Wallbom, published in the Journal of Research in Personality, who showed that mirrors reduced academic dishonesty in students by making them more self-aware. In their experiments, students who took an exam in a room decked out in mirrors were less likely to keep writing after the bell rang than those who took their tests in a normal classroom. Similarly, surveillance cameras—particularly if they’re clearly observable—should increase self-awareness and, with it, better behavior.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My closest friend since childhood recently betrayed me, after decades of trusting friendship. She has apologized sincerely, but all the confidence I had in her is still tainted. Is it rational (or helpful) to forgive people who have hurt us?

—Jamie

While it isn’t clear whether your friendship can fully recover from this incident, you clearly would be better off if you could forgive your friend. Research has shown that our health improves when we free up mental space from grudges and hate.

In a study published in 2003 in the Journal of Behavioral Medicine, Kathleen A. Lawler and colleagues interviewed 108 college students about a time when a parent or friend had deeply hurt them and measured their blood pressure at several points during the conversation. Subjects who forgave their betrayers had lower levels of blood pressure than those who hadn’t been as lenient. Even more important, college students who had more forgiving personalities overall turned over to have lower blood-pressure levels and heart rates.

Of course, forgiveness isn’t easy, but if you can pull it off, it brings real benefits.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I go out to dinner with my husband once a week, and every time, we promise to order something healthy—but when we see the menu, we get tempted and order something less virtuous but tasty. Any advice on how to show more resolve?

—Aimee

You are describing a classical case of temptation. Before you get to the restaurant, you’ve settled on a certain idea of how you want to behave—then you get tempted, and afterward, you regret your indulgences. So how can you override temptation? Just order for each other. When we order for our significant other, we aren’t tempted by taste and can instead think about their health—which is also what our spouse would want a few hours later.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

Build better health and finance tech products for humans. Join the Startup Lab.

We’re excited to announce that we’re searching for our next class of the Startup Lab, which begins October 2017. Applications are only open until June 30th at 5pm EST.

Apply to the Startup Lab now.

Our academic incubator supports problem-solvers by making behavioral economics findings accessible and applicable. See how behavioral researchers and entrepreneurs work together at the Center for Advanced Hindsight:

The Startup Lab provides:

- Ability to explore behavioral economics and learn how to leverage findings for your startup

- Opportunity to collaborate with world-renowned behavioral researchers

- Guidance and resources to run rigorous experiments

- Office space in downtown Durham, NC up to 9 months (October-June)

- Investment up to $60k

Are you insatiably curious about what drives decisions, shapes motivation, and influences behavior? Does your startup’s success hinge on the ability to affect positive behavior change that helps people live happier, healthier, and wealthier lives?

We’re looking for startups that are eager to experiment, and demonstrate a passion for building research-backed solutions to health and finance challenges.

APPLY NOW.

You only have until June 30th at 5pm EST.

To learn more, visit our FAQs (includes information on the Startup Lab investment structure and other logistics) or connect with us at startup@danariely.com.

Ask Ariely: On Dreadful Driving, Levelheaded Loving, and Successful Standing

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My daily commute takes about 40 minutes each way—and it feels even longer because so many of my honking fellow drivers are selfish and aggressive. How can we get drivers to show more respect for those around them?

—Jamie

In a word: convertibles. If we all drove rag tops with the roof down and no windows to shield us from fellow drivers, we would be far more aware of social norms and more likely to behave with some consideration for others.

Driving often brings out the worst in us, and it can be shocking to see how myopic, self-centered and unaware we become behind the wheel—from driving recklessly to cutting into lines to picking our nose.

All of this is much worse than our typical behavior when we, say, walk down a crowded public street. Pedestrians aren’t always polite, but they certainly don’t exhibit the same type of risk-taking and selfishness. Being in proximity to other people makes us more aware of our own standards of decency, and we behave accordingly.

Noise-blocking (and often darkened) windows and the controlled environment of a car create an illusion of isolation, separating us from other drivers. It lets us feel that our actions are unobserved, which makes it easier for us to ignore our own standards.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

How can I overcome my hot-and-cold attitudes toward my romantic partner? Sometimes I’m convinced that we aren’t compatible, but at other moments, I feel perfectly content with our relationship. Are these fluctuations normal?

—Tina

All relationships oscillate between good and bad—it’s just part of the deal. The question for you is whether the downsides that you are experiencing are worth it for the upsides—and whether you can deal with the fluctuations.

What I can tell you is that you shouldn’t make big decisions about the future of your relationship when you’re experiencing its bad side. When we are in a particularly strong emotional state, we often find ourselves consumed by that emotion and incapable of seeing how we could feel differently.

But emotions are transitory, and they often change more quickly than we anticipate. So assess your relationship only when you are calm and content. You’re more likely to find the right answer when you’re thinking clearly, not emotionally. Good luck.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently bought an adjustable standing-or-sitting desk, but I find that I lack the motivation to consistently stand. Any suggestions to get me on my feet more?

—Tim

When you work at a standing desk, you sometimes naturally feel the need to sit down—and once you do, of course, you’ll rarely feel the urge to stand back up. I suggest setting a timer that reminds you once an hour to put your desk back in standing position, then stand for as long as you want.

This way, you won’t sit forever. Those hourly reminders to get vertical again will probably make you more likely to stand periodically, even when you aren’t feeling the urge.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like