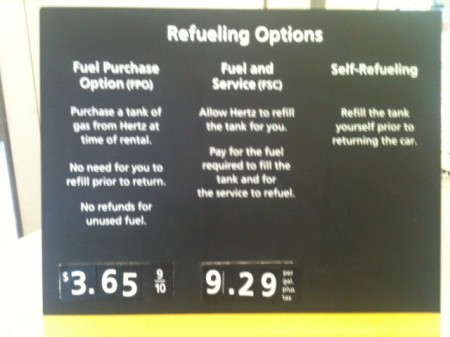

Refueling Options at Hertz

I got this picture this week. What is interesting about this price menu is that the “Fuel and Service,” priced at $9.29, is so off the scale (and so outrageous) that perhaps it makes the pre-paid option of $3.65 look attractive. After all it is about 1/3 the price of the Fuel and Service.

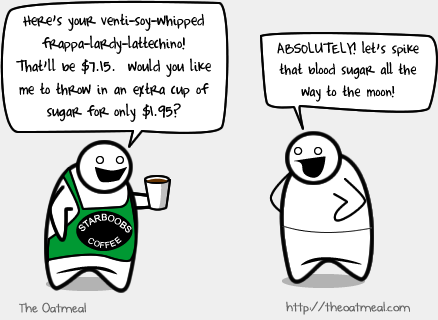

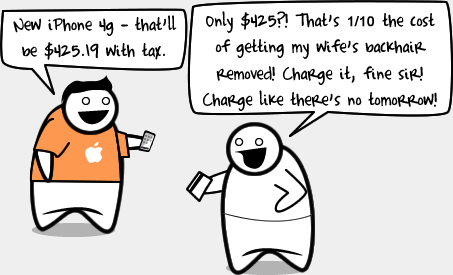

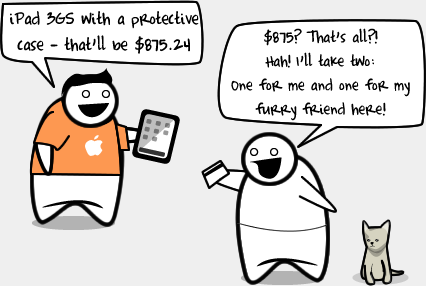

This Is How I Feel About Buying Apps

I came across a funny cartoon the other day that captures an interesting aspect of our purchasing behavior. We are perfectly willing to spend $4 on coffee (for some of us this is a daily purchase), or $500 on devices that you can argue we don’t really need. However, when it comes to buying digital items, such as apps, most of which are priced at $1, we suddenly get really cheap. Why?

http://theoatmeal.com/blog/apps

Here are some reasons. The first is that we are anchored by the price of categories, so when we think about lattes, we compare only across beverages. When we think about apps, we only compare across digital downloads. Thus, when we think about buying a $1 app, it doesn’t occur to us to ask ourselves what the pleasure that we are likely to get from this $1 app — or even what is the relative pleasure that we are likely to get from this app compared with a $4 latte. In our minds, those two decisions are separate.

So now the question becomes, why is the price anchor for apps so low? I think the answer to this is that we have been trained with the expectation that apps should be free. Having lots of free apps on the App Store is clearly advantageous for Apple, because it makes their devices more attractive. However, because FREE! is such a special, exciting price level, it makes the thought of paying even $1 for an app into an agonizing decision.

I think this could have been avoided. Imagine if instead of offering free apps on day one, Apple instead created a really low minimum price–say $0.15. Lots of people would still go for Apps at this price, but instead of being anchored to the idea that apps should be free, we would be anchored to the idea that apps should cost something. Then paying more (maybe even $2) for an app would be a simpler step, maybe one that we could take as easily as paying $4 for a latte.

What to bring for dinner

One of my long time friends just wrote me earlier today. Not seeing her for a long time I was looking forward to seeing her, and I invited her to join us for dinner on Friday night.

She was very happy to accept the invitation, and asked what she could bring. I asked her not to bring anything and just come. She wrote back insisting that she wants to bring something.

Here is my email to her ……

————————————————————————–

————————————————————————–

Is It Irrational To Give Gifts?

Many of my economist friends have a problem with gift-giving. They view the holidays not as an occasion for joy but as a festival of irrationality, an orgy of wealth-destruction.

Rational economists fixate on a situation in which, say, your Aunt Bertha spends $50 on a shirt for you, and you end up wearing it just once (when she visits). Her hard-earned cash has evaporated, and you don’t even like the present! One much-cited study estimated that as much as a third of the money spent on Christmas is wasted, because recipients assign a value lower than the retail price to the gifts they receive. Rational economists thus make a simple suggestion: Give cash or give nothing.

But behavioral economics, which draws on psychology as well as on economic theory, is much more appreciative of gift giving. Behavioral economics better understands why people (rightly, in my view) don’t want to give up the mystery, excitement and joy of gift giving. In this view, gifts aren’t irrational. It’s just that rational economists have failed to account for their genuine social utility. So let’s examine the rational and irrational reasons to give gifts.

Some gifts, of course, are basically straightforward economic exchanges. This is the case when we buy a nephew a package of socks because his mother says he needs them. It is the least exciting kind of gift but also the one that any economist can understand.

A second important kind of gift is one that tries to create or strengthen a social connection. The classic example is when somebody invites us for dinner and we bring something for the host. It’s not about economic efficiency. It’s a way to express our gratitude and to create a social bond with the host.

Another category of gift, which I like a lot, is what I call “paternalistic” gifts—things you think somebody else should have. I like a certain Green Day album or Julian Barnes novel or the book “Predictably Irrational,” and I think that you should like it, too. Or I think that singing lessons or yoga classes will expand your horizons—and so I buy them for you.

A paternalistic gift ignores the preferences of the person getting the gift, which tends to drive economists crazy, but it may actually change those preferences for the better. Of course, you might mess up by giving a paternalistic gift that someone hates, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try.

A holiday gift can straddle these categories. Instead of picking a book from your sister’s Amazon wish list, or giving her what you think she should read, go to a bookstore and try to think like her. It’s a serious social investment.

The great challenge lies in making the leap into someone else’s mind. Psychological research affirms that we are all partial prisoners of our own preferences and have a hard time seeing the world from a different perspective. But whether or not your sister likes the book, it may give her joy to think about you thinking of her.

My final category of gift is one that somebody really wants but would feel guilty buying for themselves. This category shouldn’t exist, according to standard economic theory: If you really liked it and could afford it, you’d buy it.

For me, fancy pens meet this description. I don’t use pens that much, but I’d be pleased to get a really nifty one (a Porsche 911 would be OK, too). When my students defend their dissertations, I ask everyone on the Ph.D. committee to sign the required forms with an expensive pen, and then I give the pen to the student. It’s a prototypical good gift, because it’s something that they would probably feel guilty about buying for themselves, plus it has positive associations as a memento of the day.

Behavioral economics has one more lesson for gift givers: If your goal is to maximize a social connection, don’t give a perishable gift like flowers or chocolates. True, people enjoy them, and you don’t want to impose by giving something more permanent. But what are you trying to maximize? Is your goal to avoid imposing on them or for them to remember you?

For a durable impression, better to give a vase or a painting. Even if your friends don’t like it that much, they’ll think about you more often (though maybe not in the most positive terms).

Better yet, give a gift that gets used intermittently. A painting often just fades into the attentional background. An electric mixer, when used, gets noticed.

I like to buy people high-end headphones. They get used intermittently, so I can imagine that every time you put them on, you will think of me. Also, they’re a luxury—the kind of thing that people have a hard time buying for themselves. Best of all perhaps, they’re intimate: When I give someone headphones, I can think of myself whispering in their ears.

And maybe, when they use the headphones, they’ll remember you whispering to them or even kissing their ears. Has anyone ever thought of a kiss after you hand them cash?

Happy holidays — Dan

—-

This post first appeared on WSJ.com

A quick new survey

I just posted a new study that should take you about 5 minutes to complete. If you would like to take the survey (and I would appreciate it very much), please look to the right sidebar under “Participate” and click on the “Take a quick anonymous survey” link. Thanks in advance for your help.

Irrationally Yours

Dan

Easing the Pain This Holiday Season

The image (and jingle) of the bells of Salvation Army volunteers is almost as synonymous with the holiday season as Santa Claus himself. However, the New York Times reported last month that a change may be coming to a street corner near you; the charity has begun testing the use of a digital donation system called Square that would allow passersby to donate via credit card, rather than have to worry about scrambling for loose change.

The image (and jingle) of the bells of Salvation Army volunteers is almost as synonymous with the holiday season as Santa Claus himself. However, the New York Times reported last month that a change may be coming to a street corner near you; the charity has begun testing the use of a digital donation system called Square that would allow passersby to donate via credit card, rather than have to worry about scrambling for loose change.

The article mentions two potential benefits of this kind of system. First, people are less likely to carry cash on them as they were in the past, and so Square’s credit card system provides people with a quick, simple, and convenient way to donate when they don’t have any real money handy (and with 1 in 7 Americans carrying at least 10 credit cards, this shouldn’t be a problem). Second, a credit card system would be safer because donations would not be vulnerable to theft like money in the kettle has always been.

Still, this credit card system may unintentionally have another significant benefit: it may lead people to want to donate more money than they would otherwise. There is a concept in behavioral economics known as the “pain of paying.” Simply put, it hurts us to spend (and part with) our money. And since buying things with a credit card is a less direct, less tangible way to part with money than using cash, it can feel less painful, and therefore lead people to spend more.

Assuming that this effect generalizes from buying products to donating to charities, Square’s credit card system may actually lead to larger total donations for the Salvation Army, whether it is because more people decide to donate, or because more money is donated by each individual. (Not to mention the possibility that people may feel silly choosing “loose change”-style amounts (e.g., 35 cents) to donate via credit card, and so may round up to the whole dollar for that reason alone).

So Square’s credit card system may, through behavioral economics, lead people to be more generous with their donations to the Salvation Army. If the Salvation Army uses this new system and winds up faring well, perhaps other charities should take note and consider implementing such a system as well.

Have a happy holiday season, everyone! And remember that doing the most good may be just a swipe away.

~Jared Wolfe~

Can beggars be choosers?

One day a few years ago I passed a street teeming with panhandlers, begging for change. And it made me wonder what causes people to stop for beggars and what causes them to walk on by. So I hung out for a while, engaging in a bit of discreet peoplewatching. Many people passed the beggars without giving anything, but there were a few who stopped. What was it that separated those who paused and gave money from those who didn’t? And what separated the more successful beggars from those who were less successful? Was it something specific about their situation, or their presentation? Was it the beggar’s strategy?

To look into this question, I called on Daniel Berger Jones, an acting student at Boston University who had just finished hiking around Europe. Not having shaved in months and already looking pretty scruffy, he was ready for the job (plus as part of his training to be an actor I figured it would be good for him to learn how to beg for money – at the time he did not see that particular benefit). So I found a street corner and placed him there to take on the panhandling trade. I asked Daniel to try a few different approaches to begging and to keep track of the approaches that made him more or less money. (Of course, after the experiment was over we donated all the money that he made to charity). The general setup was what we call a 2×2 design: When people walked by, Daniel would either be sitting down (the passive approach) or standing up (the active approach) and he would either look them in the eyes or not. So there were times when he was 1) sitting down and looking people in the eyes, 2) sitting down and not looking people in the eyes, 3) standing up and looking people in the eyes, or 4) standing up and not looking people in the eyes.

Daniel got to work, scrounging for money. He stayed on his corner for a while, trying the different approaches. And it turned out that both his position and his eye contact did, in fact, make a difference. He made more money when he was standing and when he looked people in the eyes. It seemed that the most lucrative strategy was to put in more effort, to get people to notice him, and to look them in the eyes so that they could not pretend to not see him.

Interestingly, while the eye contact approach was working in general, it was clear that some of the passersby had a counterstrategy: they were actively shifting their gaze in what seemed to be an attempt to pretend that he wasn’t there. They simply acted as if there was a dark hole in front of them rather than a person, and they were quite successful at averting their gaze.

At some point, something very interesting happened. There was another beggar on the street – a professional beggar – who approached young Daniel and said, “Look kid, you don’t know what you’re doing. Let me teach you.” And so he did. This beggar took our concept of effort and human contact to the next level, walking right up to people and offering his hand up for them to shake. With this dramatic gesture, people had a very hard time refusing him or pretending that they did not seen him. Apparently, the social forces of a handshake are simply too strong and too deeply engrained to resist – and many people gave in and shook his hand. Of course, once they shook his hand, they would also look him in the eyes; the beggar succeeded at breaking the social barrier and was able to get many people to give him money. Once he became a real flesh and blood person with eyes, a smile and needs, people gave in and opened their wallets. When the beggar left his new pupil, he felt so sorry for poor Daniel –and his panhandling ineptitude– that he actually gave him some money. Of course Daniel tried to refuse, but the beggar insisted.

I think there are two main lessons here. The first is to realize how much of our lives are structured by social norms. We do what we think is right, and if someone gives us a hand, there’s a good chance we will shake it, make eye contact, and act very differently than we would otherwise.

The second lesson is to confront the tendency to avert our eyes when we know that someone is in need. We realize that if we face the problem, we’ll feel compelled to do something about it, and so we avoid looking and thereby avoid the temptation to give in and help. We know that if we stop for a beggar on the street, we will have a very hard time refusing his plea for help, so we try hard to ignore the hardship in front of us: we want to see, hear, and speak no evil. And if we can pretend that it isn’t there, we can trick ourselves into believing –at least for that moment– that it doesn’t exist. The good news is that, while it is difficult to stop ignoring the sad things, if we actively chose to pay attention there is a good chance that we will take an action and help a person in need.

Flying Frustrations

A few days ago I woke up at 5:00am to drive to the airport for a trip to Chicago. I got to the airport on time, went through security and arrived at my gate with time to spare. I went through all the motions of boarding the plane, waiting to take off, and finally leaving the ground. As we were in the air, we were informed of inclement weather in Chicago and told that we would have to land somewhere else (South Bend, Indiana). So we were diverted to wait for the weather in Chicago to clear up. When the weather eventually improved, we refueled and finally took off. I missed an important lecture and felt that I had wasted most of my day.

When I think back to my day of traveling, I can’t help but cringe at the thought that my expected two-hour trip took six hours. And even though I have taken many flights longer than six hours in the past without feeling bitter, this experience was particularly annoying for two reasons.

The first reason has to do with the nagging feeling of idleness that I experienced when I was stuck on the plane on the ground, just waiting. And this reminds me of a lesson on the design of air travel: There once was a clever engineer who noticed that the carousels for luggage are spaced at different distances from different gates – some farther and some closer to where the passengers were deplaning. And this engineer redesigned the allocation of carousels such that they minimized the distance to their gate, and therefore minimized the amount of walking that passengers would have to do to pick up their luggage. A few airports implemented this highly efficient system and patted themselves on the back. They were very pleased with their improvement – that is, until people started complaining.

Of course, everything that the engineer predicted was true. By refining the assignment of carousels to match up with their corresponding gates, people had to walk less and could get to their luggage faster. The problem was that this system worked too well, and passengers were beating their luggage to the carousels. When they arrived, they had to twiddle their thumbs while they waited for their luggage to catch up with them.

Think about these two ways to get your luggage: With the original airport design, you walk ten minutes, but when you finally get to the carousel, your baggage gets there a minute after you (taking 11 minutes). In the other, you walk three minutes, but when you arrive you have to wait five minutes for your luggage (taking 8 minutes). The second scenario is faster, but people become more annoyed with the process because they have more idle time. As Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Sr. noted, “I never remember feeling tired by work, though idleness exhausts me completely.”

The “good news” is that airports quickly reverted to their former (inefficient) system, and we now walk farther to our suitcases just to avoid the frustrations of idleness.

Now, it’s one thing to waste time, but it’s particularly bothersome when you feel like you are backtracking. In my case of flying to Chicago, the trip took a detour that sent me in away from my final destination. This is the second reason that my flight experience was so irritating — it included an element of backtracking in the opposite direction of my goal.

Let’s think about this idea with another example. Imagine that you are taking the train from point A to point B. You can choose between two paths, both taking four hours but with one key difference: In Trip 1, you take the slow train from point A to B. In Trip 2, you take the fast train, but the train passes B and continues for another hour until it gets to C, and then you change trains and backtrack for an hour to B. It turns out that the second approach is more irritating, even though we should care only about the time and not the direction of progress.

My flight had both of these annoying principles, idleness and backtracking. We wasted lots of time, and we were diverted in the opposite direction. Now, I am positive that this will not be the last time that I experience these travel elements, so the question is how I will deal with these irritations in the future. To overcome the feeling of idleness, I can try finding something to make me feel that the time is spent productively (maybe I should start making lists of things to do and use idle time to manage these lists on my phone). And what about overcoming the annoyance of backtracking? Maybe ignorance really is bliss — and the only solution is not to think about the route that we are taking.

Taxes: Hate ’em? Love ’em?

Taxes: Hate ’em? Love ’em? More, importantly, are they fair? We want to hear from you about this hotly contested topic of national debate!

We suspect that taxes might be influencing us – especially, our attitudes and productivity – in more ways than we realize. Help us find out, by taking this quick survey: https://danariely.qualtrics.com/SE/?SID=SV_didFPT05NQ1LsXy

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like