Why you should watch football until the very end

By Wendy De La Rosa, Dan Ariely, and Kristen Berman

During the last month, the World Cup has captivated the globe, including our team at Irrational Labs. We have watched all 64 games and rejoiced / suffered through each of the 171 goals (not counting penalty kicks). This 2014 FIFA World Cup turned out to be an entrancing tournament: Eight of the “Round of 16” matches went into overtime, four went to penalty kicks, and the final match ended with Germany scoring in the 113th minute!

When we watched the now infamous Germany – Brazil game, we couldn’t help but come up with some interesting behavioral questions. When German midfielder Thomas Mueller scored the first goal against Brazil 11 minutes into the game, many of our Brazilian friends said this is just the start of the game.

And while we all know what happened, we started thinking: Were our Brazilian friends onto something – are there more or less goals and attempts late in the game?

One would stipulate that there is no difference in scoring between the first and the second half. Every goal matters equally, regardless of when it is scored, and players should attempt to score with the same amount of effort and success over time.

Another hypothesis is that fewer goals are scored in the second half as players fatigue Unlike basketball, where players are often substituted in and out, most of the football players are on the field for the full 90 minutes of play (sometimes 120 minutes if it goes to overtime).

Yet another hypothesis is that players score more goals in the second half as they are closer to the end of the game. Motivation research suggests that agents are more motivated as they near the end of their stated objective, whether a marathon or a life altering championship.

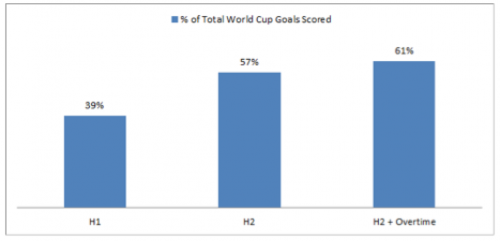

It turns out our Brazilian friends were right; more goals are scored in the second half! Of the 171 goals scored in the World Cup, 39% of the goals were scored in the first half, 57% in the second half, and 61% in the second half when we include overtime.

After learning that players score more goals in the second half, we wanted to know why. There are two ways to increase goals scored: increase attempts or increase skill (measured as goals / attempts). Which one is at play here?

The skill hypothesis stipulates that players are “super humans” who perform best when they are under pressure. Consider German Mario Gotza, a substitute midfielder, scoring the game winning goal against Argentina just seven minutes before the end of the match.

To answer this question, we compared a team’s skill in the entire game to a team’s skill in the last 15 minutes of a game. Our analysis showed that there is no statistical difference in skill when you compare these 15 minutes. This is consistent with an interesting study done by Dan Ariely and Racheli Barkan, where they studied the shooting percentages of “clutch players.” Clutch players are NBA players who are widely regarded as “basketball heroes who sink a basket just as the buzzer sounds.” As it turns out, clutch players do not become better basketball players as the pressure increases in the last few minutes of critical games. Basketball players, like our football players, do not increase in skill towards the end of the game.

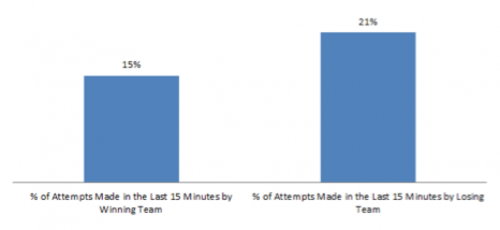

So if it’s not a question of increased skill (% conversion), it must be a question of effort (number of attempts). Given this finding, we decided to analyze the number of attempts made by players, and whether they increase as the game wears on. Which team is attempting the most goals at the end of the game? One hypothesis is that the leading team increases their attempts as they are more confident and have strong momentum behind them. The other hypothesis is that the trailing team would attempt more goals at the end of the game because the cost of losing is more salient to them.

We can see loss aversion playing out in golf green. According to researchers, Devin Pope and Maurice Schweitzer, “Golf provides a natural setting to test for loss aversion because golfers are rewarded for the total number of strokes they take during a tournament, yet each individual hole has a salient reference point: par (the typical number of shots professional golfers take to complete a hole).” After analyzing PGA Tour putts (the last shot before a hole), they noticed that golfers are extremely loss averse. Golfers make putts for birdie (one shot less than par) significantly less often than identical-length putts for par (getting to par). The researchers estimate that this loss aversion costs the average pro golfer about one stroke per 72-hole tournament, and the top 20 golfers about $1.2 million in prize money a year.

Does this theory hold true in football? After analyzing the data, we found that during the last 15 minutes of each game, number of attempts made by the trailing team (as a percentage of their total attempts made during the game) increase, while the number of attempts made by the winning team decreases.

Why is this? We believe we can explain this phenomenon with loss aversion. Loss aversion is the behavioral economic concept that states that we value losses more than we value commensurate gains. The other stipulation in loss aversion theory states that we are risk seeking in losses and risk averse in gains. In other words, our risk appetite increases when we are losing. This phenomenon is known as “risk shift.”

The feeling of loss aversion is heightened in football. Think about the cost of a goal in football compared to the cost of a basket in basketball. Because goals are so difficult to make, the cost of giving up a goal is greater than the cost of not making a goal. Thus, teams are naturally more defensive, focused on avoiding “a goal” or a “loss” much less than “scoring” or “gaining” for most of the game.

Loss aversion is a powerful concept, and we are all susceptible; even world class football players. So to go back to our Brazilian fans, expecting more effort as the game continues is a reasonable expectation. Unfortunately, and as the Brazilian fans found out, sometimes effort is not enough.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like