Finance, Meet Pharma

We’ve known for a while that both the processes and products of the pharmaceutical industry need to be regulated. The roots of this regulation stretch back over a century, but it’s been since the Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments were passed in 1962 in response to thousands of severe birth defects caused by the drug thalidomide that drug manufacturers were for the first time required to prove the effectiveness and safety of their products to the FDA before marketing them. Since that time, we’ve created huge obstacles in terms of time, money, and evidentiary rigor between drug manufactures and the market; on average, it takes about 10-15 years and hundreds of millions of dollars for a drug to make it from the lab to the pharmacy. And as we come to a greater understanding about conflicts of interest and prescribing patterns, we also regulate the activities of pharmaceutical companies at even smaller level, such as when and to whom they can give pens or free lunches.

In stark contrast, we have the financial industry. In this domain, no one needs to prove the safety or effectiveness of financial products such as derivatives and mortgage-backed securities. This is because we make two major assumptions about such products based on economic theory: we presume first that they have sound internal logic and second, that the market will correct problems and mistakes if something goes awry with one of these new inventions.

In theory we could make the same argument for pharmaceutical products as well. Medications are also developed based on logic—in this case chemical and biological—and a group of experts assume that they will be effective based on this logic. We can also assume that the market would weed out bad medications, just as it weeds out unsuccessful companies and products. How would it do this? Well, people who take bad medications would become ill or die, other people would find out, and over time this process would preserve the demand for medications that work well—the same logic that is applied to financial products. Despite these parallels, there’s an incredible lack of symmetry in how we view regulating these markets.

People remain highly suspicious of one market (pharmaceutical), and far less so of the other (financial), but when we compare the systems in broad strokes, their similarities are evident. A paper I read recently got me thinking more about this comparison. In both cases, the industries in question get more money if people use more of their products, and both use salespeople to convey information about their products to consumers. So far that’s pretty standard fare in business. Less common is the similarity that these salespeople have incentives such that they benefit from selling the product, but lose nothing when it fails. Moreover, in both cases the product is complex and difficult to understand, even at the expert level. Additionally, there is substantial asymmetry in the knowledge of salespeople versus that of consumers. And in both cases, the stakes are very high, with physiological health and financial health in question. And while death rarely occurs as a direct result of financial products, the damage they can do is immense (see the financial crisis of 2008).

Yet we apprehend the dangers inherent in a free pharmaceutical market while remaining generally oblivious to those in the financial. No one protests along libertarian lines of letting pharma be free, or shouts from a podium that if the government just stayed out of our treatments and medications, amazing and innovative new cures would suddenly appear. Why then don’t we see the need to regulate the financial market?

I believe that one of the reasons for this discrepancy is that the casualties and damage done in the pharmaceutical domain are far more apparent. When things go badly in medicine, it’s easier for us to quantify them and make clear causal connections. Whereas in the financial market it’s generally the case that lots of people lose some money, but people rarely lose everything. Moreover, in the financial market, there are never just losers, there are always winners as well—someone will gain a lot from a losing transaction, and that’s frequently chalked up to how the system works. With pharmaceutical losses, the injury or death of patients far exceeds any gain the company might make (and then lose in litigation). Also, with medications, the counterfactual is generally much stronger. There are people who took a drug and those who didn’t, and often a clear comparison of the difference emerges. In economics it’s far more difficult to make a causal connection, after all, there is still debate over whether the first and second bailouts helped anyone other than the institutions that got paid directly.

Given the similarities between the markets, and the differences in how we tend to regard them, I think we need an FDA-like entity and process for financial products, because if we don’t have a counterfactual, we can’t compare and measure the value of their products. We could call it the FPA, for Financial Product Administration. One example of a financial tool that the FPA could test is high frequency trading. Companies are going all out to profit by being the fastest to buy and sell stocks, owning them for fractions of a second; they even go so far as to buy buildings closer to the stock market to make trading faster. The logic behind high frequency trading is that companies can take advantage of even tiny price fluctuations. And it’s possible that in principle they’re adding to the efficiency of the market, but it’s more likely that they increase volatility, and frighten people off the market, and therefore have a negative effect. It’s an understatement to say that this strategy is focused on the short term, whereas investment ideally is about a longer-term commitment. But regardless of one’s beliefs on whether high frequency trading is ethically sound, it would be nice to know for sure if it makes the markets better or worse off before allowing it.

By the way, one thing I appreciated most about the paper that inspired this post is that the authors are from the University of Chicago—home of the free market champions. That’s a departmental seminar I wouldn’t mind sitting in on.

An Alternative to Calorie Labels

We just published a new paper:

A top cause of preventable death, obesity is a growing threat to an able-bodied, functioning society. Simply put, overeating is one of the biggest contributions to the obesity epidemic, and despite widespread efforts to promote health education, there may be better ways to combat this problem than by giving people nutritional information and relying on them to use that information to make wise choices. After all, we live in a country where chef Jamie Oliver’s shocking chicken nugget demonstration was absolutely no deterrent to the appeal of a fried blend of gooey chicken carcass.

If even this shocking intervention had no effect, we may need to do more than post calorie labels, a movement that (albeit well-intended) has seen limited success (see 1,2,3). Traditionally, such interventions are more successful at changing attitudes than actual behaviors, and when it comes to health — attitudes and behaviors don’t always go hand in hand.

Of course, we know that just thinking about exercise and eating healthy will not keep us healthy – we can’t lose weight by intending to use the treadmill. We need to put on our gym shorts and start jogging. With food, we can start by simply eating less.

Janet Schwartz and I, along with Jason Riis and Brian Elbel, tested out an alternative to calorie labeling – merely asking customers at a fast food restaurant (with and without a small incentive) if they would like to downsize their side dishes (by taking a half portion of an excessively large high-carbohydrate side dish). We carried out this intervention before and after calorie labels were put in place, and found that while calorie labels had no effect on the number of calories consumed, the offer to downsize did! As much as a third of the customers who were given the offer decided to take less food (compared to ~1% who asked to downsize on their own) and consequently ate less (yes, we even weighed their leftovers), showing that a simple offer to downsize can go a long way toward encouraging a healthier diet.

The conclusion: Offering people a chance to exercise self control can be effective, but we need to stop people, slow them down and offer them to take a better path at the moment when they are placing their order.

———

(1) Downs JS, Loewenstein G, & Wisdom J. (2009). The psychology of food consumption: strategies for promoting healthier food choices, American Economic Review, 99(2), 1-10.

(2) Elbel B, Kersh R, Brescoll V, & Dixon LB. (2009). Calorie labeling and food choices: A first look at the effects on low-income people in New York City, Health Affairs, 28(6), 1110-21.

(3) Bollinger B., Leslie P. & Sorensen AT. (forthcoming). Calorie Posting in Chain Restaurants. AEJ: Economic Policy.

Audience with a Dragon Tattoo

I’ve explored the power of free in the context of tattoos before, and anyone who saw last years’ comedy Bridesmaids no doubt laughed at this particularly memorable scene. But this story out of the Netherlands caught me a little off guard just the same. First, consider what you would do for a year’s worth of free movie tickets. Or if you like live music, tickets to your favorite venue. Would you pay $200? Would you eat a bag of (nonpoisonous) insects?

Well, the Unlimited Movies Cinema in the Netherlands has offered moviegoers the opportunity to see free movies for an entire year—all they have to do is get the theater’s logo (a dog-like creature flying under a banner of unfurled film reel) tattooed on their body (for pictures, check this page out). The offer is part of a promotion for the latest movie in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo series.

I developed an appreciation for the surprising power of FREE! from the experiments my colleagues and I conducted on how people respond to things when their cost is zero (included in Predictably Irrational). For instance, when we set up a temporary candy stand and sold mouthwatering Lindt truffles (which usually cost around 50 cents) for 15 cents and ho-hum Hershey Kisses for 1 cent, 73% of the chocolate-lovers who stopped by made the rational decision and chose the superior and highly discounted Lindt truffles. But when we lowered the price by 1 cent for each item—resulting in a cost of 14 cents and 0 cents respectively—suddenly demand reversed and 69% of consumers chose the free Kisses.

The power zero exercises over people’s choice in chocolate nicely demonstrates the irrational draw of free things, but it’s still difficult to know what to make of people getting a cinema logo (and not the most aesthetically pleasing one at that) permanently inked on their body for a single year of free movies. While according to the story, only 18 people have elected to exchange skin space for free movies, one has to ask whether the wonders of free will ever cease…

Special Deals at Whole Foods

Jared Wolfe, one of the students working with me, took the following pictures at Whole Foods a few days ago. They illustrate amazing creativity in defining what the term “a deal” means.

1) Regular price is $1.99 and the Sale price is? Two of the same item for $5 — which according to Whole Foods’ quick calculation is a savings of $1.02. Amazing.

2) Regular price is $3.99 and the Sale price is? $3.99 — thankfully this time they did not add any amount to the savings.

What I am wondering is how many people just look for the orange tags and the Sale signs without even looking at the details. I suspect that this is very common, particularly in a busy and hectic grocery store and particularly when we buy many items that each of them by itself is not very expensive.

FREE! in Swedish Medicine

I recently learned of an interesting innovation in medical pricing coming from Sweden. This pamphlet from the healthcare authority states (translated): “If you have a respiratory problem and you don’t take antibiotics for it during your first visit to the doctor, you have the right to a second visit within five days free of charge”.

This approach is using the power of FREE! in an attempt to get people to reduce their use of antibiotics. But, I wonder if this approach might be too powerful, such that it will get people who do need antibiotics not to get them. And I also wonder whether this approach will be particularly effective on people who have less money — which might not be ideal.

The Economics of Sterilization

When it comes to sterilization, Denmark has had a rather turbulent history. In 1929, in the midst of rising social concerns regarding an increase in sex crimes and general “degeneracy,” the Danish government passed legislation bordering on eugenics, requiring sterilization in some men and women. Between 1929 and 1967, while the legislation was active, approximately 11,000 people were sterilized – roughly half of them against their will.

Then, the policy was changed so that sterilization was still available, still free, but not involuntary. And as you might expect, the sterilization rate in Denmark dropped down dramatically – and stayed this way until 2010.

Now we come to 2010. In only a few short months, the sterilization rate increased fivefold. No, this was not a regression to the old legislation; it was a result of free choice…

What happened? Last year, the Danish government announced that sterilization, which had been free, would cost at least 7,000 kroner (~$1,300) for men and 13,000 kroner (~$2,500) for women as of January 1st, 2011. Following the announcement, doctors performing sterilizations found that their patient load suddenly surged. People were scrambling to get sterilized while it was still free.

Now, it could be that the people who were already planning on getting sterilized at some point in the future just made their appointments a bit sooner, and conveniently saved some money. But I can also imagine that (much like our research on free tattoos) there were many people who did not really think much about sterilization before the price change, but were so averse to giving up such a good deal that it pushed them to take the offer and undergo a fairly serious procedure.

And although we usually don’t think about sterilization as an impulse purchase, it might just become one when a free deal is about to be snipped.

Amy Winehouse & responsibility

The recent death of Amy Winehouse should make us pause and consider the question of personal and shared responsibility. Was she solely responsible for her tragic outcome? Or was it somewhat the fault of the people around her? How do we want to think about the state of mind of a drug addict? And what does that say about their ability to make good decisions and hence their responsibility?

I am almost sure that if I were a jury member being presented with a case of a drug addict who committed a crime while in a highly emotional state of drug craving — that I would equate this state of mind to temporary insanity, and would find this to be a mitigating circumstance.

And if being in a state of drug craving can be considered a mitigating circumstance, shouldn’t this tell us that we should not expect too much personal responsibility from people who are in this state of mind? And shouldn’t the people around them (particularly the ones working with / for them) take control? There is a very nice saying that “friends don’t let friends drink and drive,” and I suspect that this rings even truer of drug cravings.

—

P.S. To clarify, my point here is not that Amy Winehouse is not to blame for her decisions, or that her friends are. Rather, I think that we need to back down from our chronic obsession with personal responsibility and realize that there are times when it is necessary to step in to help people who are not in a state to make the right decisions for themselves. Who knows, maybe the next Amy Winehouse’s daddy will try a little harder to keep her in rehab when she won’t go, go, go.

Wait For Another Cookie?

The scientific community is increasingly coming to realize how central self-control is to many important life outcomes. We have always known about the impact of socioeconomic status and IQ, but these are factors that are highly resistant to interventions. In contrast, self-control may be something that we can tap into to make sweeping improvements life outcomes.

If you think about the environment we live in, you will notice how it is essentially designed to challenge every grain of our self-control. Businesses have the means and motivation to get us to do things NOW, not later. Krispy Kreme wants us to buy a dozen doughnuts while they are hot; Best Buy wants us to buy a television before we leave the store today; even our physicians want us to hurry up and schedule our annual checkup.

There is not much place for waiting in today’s marketplace. In fact you can think about the whole capitalist system as being designed to get us to take actions and spend money now – and those businesses that are more successful in that do better and prosper (at least in the short term). And this of course continuously tests our ability to resist temptation and for self-control.

It is in this very environment that it’s particularly important to understand what’s going on behind the mysterious force of self-control.

Several decades ago, Walter Mischel* started investigating the determinants of delayed gratification in children. He found that the degree of self-control independently exerted by preschoolers who were tempted with small rewards (but told they could receive larger rewards if they resisted) is predictive of grades and social competence in adolescence.

A recent study by colleagues of mine at Duke** demonstrates very convincingly the role that self control plays not only in better cognitive and social outcomes in adolescence, but also in many other factors and into adulthood. In this study, the researchers followed 1,000 children for 30 years, examining the effect of early self-control on health, wealth and public safety. Controlling for socioeconomic status and IQ, they show that individuals with lower self-control experienced negative outcomes in all three areas, with greater rates of health issues like sexually transmitted infections, substance dependence, financial problems including poor credit and lack of savings, single-parent child-rearing, and even crime. These results show that self-control can have a deep influence on a wide range of activities. And there is some good news: if we can find a way to improve self-control, maybe we could do better.

Where does self–control come from?

So when we consider these individual differences in the ability to exert self-control, the real question is where they originate – are they differences in pure, unadulterated ability (i.e., one is simply born with greater self-control) or are these differences a result of sophistication (a greater ability to learn and create strategies that help overcome temptation)?

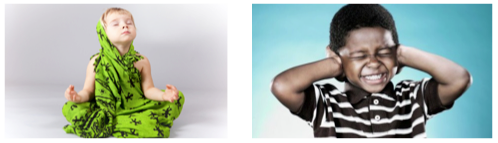

In other words, are the kids who are better at self control able to control, and actively reduce, how tempted they are by the immediate rewards in their environment (see picture on left), or are they just better at coming up with ways to distract themselves and this way avoid acting on their temptation (see picture on right)?

It may very well be the latter. A hint is found in the videos of the children who participated in Mischel’s experiments. It’s clear that all of the children had a difficult time resisting one immediate marshmallow to get more later. However, we also see that the children most successful at delaying rewards spontaneously created strategies to help them resist temptations. Some children sat on their hands, physically restraining themselves, while others tried to redirect their attention by singing, talking or looking away. Moreover, Mischel found that all children were better at delaying rewards when distracting thoughts were suggested to them. Here is a modern recreation of the original Mischel experiment:

A helpful metaphor is the tale of Ulysses and the sirens. Ulysses knew that the sirens’ enchanting song could lead him to follow them, but he didn’t want to do that. At the same time he also did not want to deprive himself from hearing their song – so he asked his sailors to tie him to the mast and fill their ears with wax to block out the sound – and so he could hear the song of the sirens but resist their lure. Was Ulysses able to resist temptation (the first path)? No, but he was able to come up with a very useful strategy that prevented him from acting on his impulses (the second path). Now, Ulysses solution was particularly clever because he got to hear the song of the sirens but he was unable to act on it. The kids in Mischel’s experiments did not need this extra complexity, and their strategies were mostly directed at distracting themselves (more like the sailors who put wax in their ears).

It seems that Ulysses and kids ability to exert self-control is less connected to a natural ability to be more zen-like in the face of temptations, and more linked to the ability to reconfigure our environment (tying ourselves to the mast) and modulate the intensity by which it tempts us (filling our ears with wax).

If this is indeed the case, this is good news because it is probably much easier to teach people tricks to deal with self-control issues than to train them with a zen-like ability to avoid experiencing temptation when it is very close to our faces.

*********************************************************

* Mischel W, Shoda Y, Rodriguez MI (1989) Delay of gratification in children. Science. 244:933-938.

** Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Houts R, Poulton R, Roberts B, Ross S, Sears MR, Thomson WM & Caspi A (2011) A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth and public safety. PNAS. 108:2693-2698.

Physician-Assisted Suicide and Behavioral Economics

By Arjun Khanna

As the American population ages, the debate about the ethics of physician-assisted suicide for terminal patients becomes more important.

Proponents of legalizing of physician-assisted suicide argue the practice is ethically justifiable because it can alleviate prolonged physical and emotional suffering associated with debilitating terminal illness. Opponents claim that legally sanctioned lethal prescriptions might destroy any remaining desire to continue living – a sign of society having “given up” on the patient.

Ultimately, these arguments rest on differing opinions regarding the effect of this policy on the patient’s wellbeing. The challenge, then, is to determine how legalization of physician-assisted suicide would affect the wellbeing of terminally ill patients and their medical decision-making.

Outside of philosophical arguments, examination of an interesting finding regarding physician-assisted suicide – know as “The Oregon Paradox” – can add an interesting dimension to the debate. The paradox is the finding that when terminal patients in Oregon receive lethal medication (under Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act), they often feel a sense of greater wellbeing and a desire to live longer. In 2010, of 96 patients requested lethal medication, only 61 actually took it. Even more interesting are the many anecdotal accounts of terminal patients, upon receiving lethal medication, that feel a surge of wellbeing and a desire to persevere through their illness.

Why is this this the case? Looking at this question from an expected-utility perspective suggests that given the option to terminate their own life, terminal patients will decide how long they want to live by comparing the value they expect to gain from the rest of their lives to the expected intensity of their suffering. At the point where future utility is expected to be negative – that is, when the patient’s condition becomes so intolerable that living any longer is not worth the cost – the patient would choose to end life if the option were available.

The critical point from this perspective is that patients choose the amount of time they are willing to continue living with their illness, which will depend how quickly they deteriorate. If the rate of deterioration is slower than expected, then patients should delay terminating their lives; if the rate of deterioration is faster than expected, patients should desire to end their lives quicker.

But now let us say that patients have been prescribed lethal medication and have the option of ending their lives at any point of their choosing. As before, patients don’t want to choose a time too soon or too distant, but with the power to control the end of their lives they no longer have a reason to err on the side of haste! The patients can now wake up every day with the comfort of knowing that they do not have to suffer through pain or stress they might find intolerable.

Being given the option to determine the time of our own death can transform patients from powerless victims of their illness to willing survivors of it. Together, the importance of feeling in control and the ability to reduce (but not eliminate) uncertainty about rate of deterioration adds an interesting new dimension to the underlying ethical debate and seems to provide credence to the benefits of legalized physician-assisted suicide.

It is clear is that we need a greater understanding of the decision-making of patients at the end of their lives, and that with this improved understanding we can construct policy to better protect their wellbeing (for an interesting recent movie on this topic see “How to Die in Oregon”).

———————–

References:

Lee, Li Way, 2010. “The Oregon Paradox” Journal of Socio-Economics. 39(2):204-208.

Turman, S.A., 2007. The Best Way to Say Goodbye: A Legal Peaceful Choice at the End of Life. Life Transitions Publications.

A tribute to my son

A tribute to my son, Amit who is 8 years old — and came up with a very similar poem by himself today

Sick

By Shel Silverstein

‘I cannot go to school today, ‘

Said little Peggy Ann McKay.

‘I have the measles and the mumps,

A gash, a rash and purple bumps.

My mouth is wet, my throat is dry,

I’m going blind in my right eye.

My tonsils are as big as rocks,

I’ve counted sixteen chicken pox

And there’s one more-that’s seventeen,

And don’t you think my face looks green?

My leg is cut-my eyes are blue-

It might be instamatic flu.

I cough and sneeze and gasp and choke,

I’m sure that my left leg is broke-

My hip hurts when I move my chin,

My belly button’s caving in,

My back is wrenched, my ankle’s sprained,

My ‘pendix pains each time it rains.

My nose is cold, my toes are numb.

I have a sliver in my thumb.

My neck is stiff, my voice is weak,

I hardly whisper when I speak.

My tongue is filling up my mouth,

I think my hair is falling out.

My elbow’s bent, my spine ain’t straight,

My temperature is one-o-eight.

My brain is shrunk, I cannot hear,

There is a hole inside my ear.

I have a hangnail, and my heart is-what?

What’s that? What’s that you say?

You say today is…Saturday?

G’bye, I’m going out to play! ‘

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like